The CIO’s Take:

Investors have been on a rollercoaster in recent weeks. The bulls looked to be in full control going into the end of last year, but a weak start to 2024 saw stocks surprisingly miss out on the proverbial “Santa Claus rally.” Then, after a rough first few days last week, equities sharply rebounded, with the NASDAQ up 2.6% by Friday’s close. What explains all this volatility? We see it as whipsawing market sentiment, which has been bouncing back and forth between optimism over solid data on the US economy, which makes a soft landing more likely, and disappointment that strong growth likely diminishes the prospects for rapid easing. Given how much optimism was baked into prices at the end of 2023, we believe there’s more downside risk at this point, with sticky inflation—and geopolitical shocks like Red Sea attacks and the resultant surge in container shipping costs—threatening to force major economies’ central banks to talk down hopes for fast and deep rate cuts this year. Based on these expectations, we see equity valuations as a little too rich and yields as a little too low, and maintain our defensive stance into the end of January.

Strong macro data raises questions on cuts

As we’ve discussed ever since the Fed pivoted in its dot plots a month ago and markets got their hopes up for a quick move to easing, much will depend on how the data look in the months ahead. Regardless of one’s theory for the FOMC’s abrupt shift in messaging—are they confident inflation is coming down amidst a soft landing, or are they worried about the US economy suddenly going off the rails?—as long as the macro picture looks super-strong, it’s hard to see rates coming down as fast as traders have been pricing since December. Rayliant’s approach is inherently “data-driven,” and we’ve heard the Fed use that phrase, too, in describing their approach to monetary policy. There’s a reason those quarterly dot plots change, and investors should be aware that the happy forecasts stemming from December’s FOMC are subject to revision. As such, we intend to pay especially close attention in coming weeks to where data are trending: not just with respect to inflation, but also the job market, business conditions, and consumer spending, that will factor into the Fed’s decision-making.

Retail sales show consumers hanging on

To that end, an issue that’s increasingly concerned us is how stretched American consumers appear to be. We’ve watched for months as credit card balances ballooned and “buy now, pay later” activity surged; then last week, amidst big banks’ earnings reports, we got some more confirmation of households’ somewhat extended position. As consumers feel the squeeze, can spending keep up? According to last week’s retail sales data for December, the answer seems to be “so far, so good.” Based on data from the Commerce Department, reported last Wednesday, retail sales rose by 0.6% in the final month of the year, beating economists’ forecast of a 0.4% rise and clocking in at 5.6%, year-over-year, more than tracking with inflation. Data from last week’s release of the Federal Reserve’s “Beige Book”—a summary of business conditions across the twelve Fed districts, compiled by the Philadelphia Fed and anecdotally receiving considerable weight in the FOMC’s deliberations—highlighted one potential vulnerability: although the general read was stable, nearly every district cited one or more signs of a cooling job market. That observation seems at odds with December’s nonfarm payroll, making it all the more worth watching.

Timeline for cuts seen shifting

Throughout this policy cycle, we have watched as markets consistently second-guessed the US central bank’s official statements and off-the-cuff remarks by Fed officials. Sometimes, that volatile “recalibration of expectations” has felt a bit self-serving, in our view, driven by a confirmation bias directed at validating bullish animal spirits. Not that we’re judging: We at Rayliant likewise have to be vigilant to avoid interpreting new data in ways that unduly support our currently cautious view! Other times, changes in market expectations come off as a more earnest attempt at zeroing in on a definitive reading of the Fed’s game plan, even when that read is disappointing. In recent days, ever since the market leapt out to exceedingly optimistic expectations for fast and deep rate cuts in the next few months, we’ve seen more of this latter type of sincere reevaluation. With data on a range of economic quantities of interest—from inflation to the labor market to consumer spending—spiking up at the end of the year (see below), markets have revised their projected timetable for easing, with the implied probability of no rate cuts by March rocketing from under 10% in late-December to nearly 53% as of last Friday, according to the CME Group.

Bottom line, as the US economy operates near full capacity, with falling energy and goods prices boosting consumer’s capacity to spend, the Fed surely recognizes that rate cuts now could inadvertently reignite inflationary pressures. That scenario echoes historical instances where premature central bank action led to prolonged problems fighting rising prices. While the expectation of quicker cuts initially buoyed risk assets like equities, how long those gains hold—and, indeed, whether they sharply reverse—is uncertain. While we, like many analysts, have taken better macro data and the Fed’s shift in tone to imply a higher likelihood of a good year in 2024, we remain cautious relative to what we see as a consensus overreaction to the positive side.

December CPI surprises hit UK, Canada

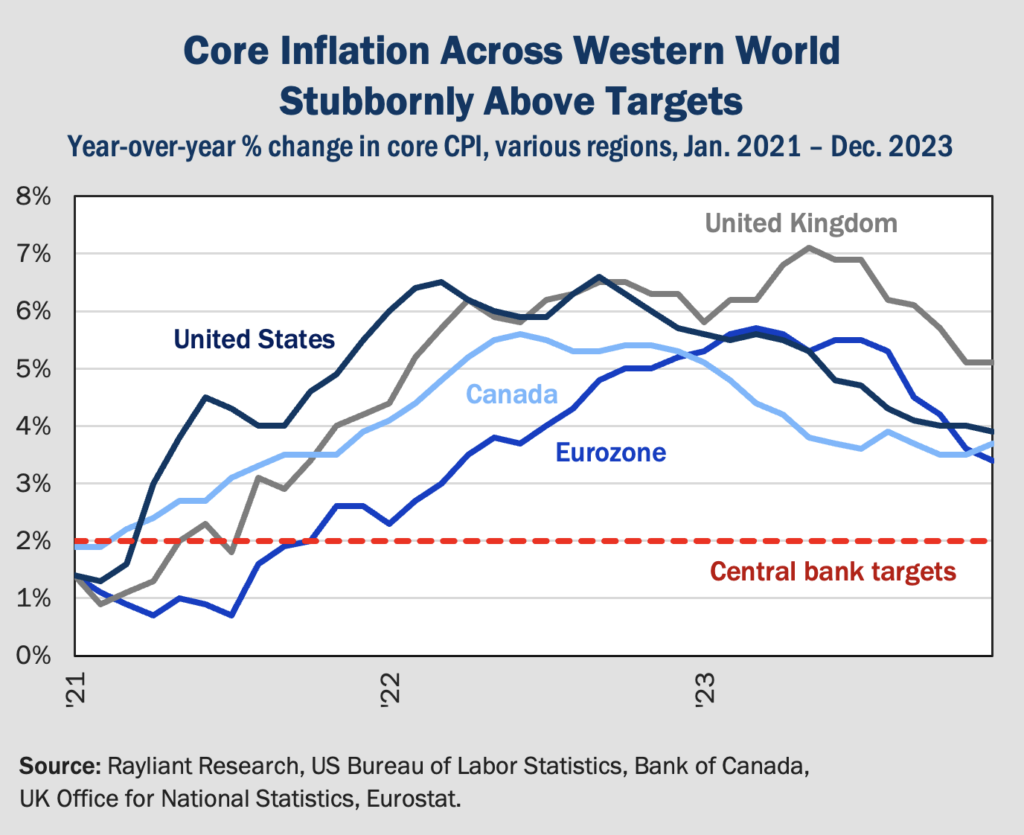

Just as investors in the US parse data on Fed policy, participants in other markets around the world have been repricing the possibilities for central bank easing in response to developments in the overall macro picture, including with respect to inflation—which, despite coming down significantly in major Western economies, is still well above the typical 2% target (see below). It was a rollercoaster ride for France’s CAC 40 and Germany’s DAX Index last week, with both indices ending down a little over -1%, and European bonds sold off as ECB President Christine Lagarde indicated a delay in the anticipated start to easing by the European Central Bank from spring to summer. Likewise, the first spike in UK inflation in ten months dampened rate cut expectations across the Channel, as headline, core, and services metrics all surprised to the upside. Canada’s core inflation rate surged in December, underscoring the challenging final stretch in central banks’ campaigns to restore price stability, something we’ve often discussed, and a difficulty that obviously applies in the US, too.

Central banks increasingly cautious

In fact, we see stickiness in price pressures as one of the greatest threats to a favorable outcome this policy cycle. In the case of UK inflation, for example, most improvement so far has come from falling energy costs and a leveling out of food prices, while core inflation (plotted above) flatlined at 5.1% in December. In Canada, the December report on prices showed shelter inflation remained the biggest driver of core CPI increases, exacerbated by a supply shortage and high levels of immigration. Such trends undoubtedly make central banks nervous about easing prematurely and adding fuel to the fire. Even in acknowledging the likelihood of a summer rate cut, President Lagarde’s tone was cautious, with the qualification that any easing was contingent on improvement in wage pressure data by late spring. She also emphasized that overly optimistic expectations for aggressive easing can have a detrimental influence on the bank’s fight against inflation, which ultimately feeds back into central bank policy. That’s a point we’ve made in past Perspectives, noting that despite Fed tightening, financial conditions on-the-ground have been effectively loosened as a result of that second-guessing of the Fed we mentioned before.

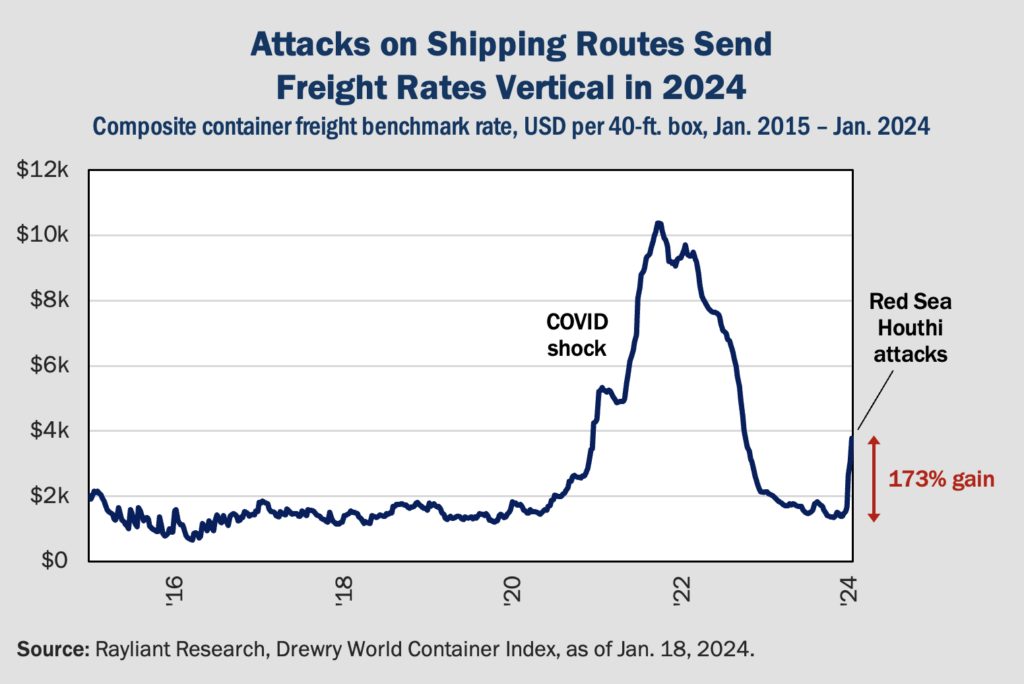

Houthi attacks see shipping costs soar

Much of the progress major economies have made against inflation so far is on the goods side, as pandemic-era supply chain disruptions eased. One implication is that such inflation could snap back if those logistical disturbances were to reemerge. Markets got some bad news on that front when the Houthi militia in Yemen began firing on ships passing through the Red Sea, in what they have described as a response to Israel’s siege of Gaza. That stretch of water turns out to be a key maritime route leading ships to the Suez Canal, accounting for some 10% of global shipping by volume, according to Clarksons. While the US and UK launched air strikes on the Houthi rebels last week, transport firms weren’t taking any chances and had already begun rerouting ships around Africa—the Cape of Good Hope route—which is not only much longer, but also requires disproportionately more fuel to navigate and poses its own risks, including West African piracy and more difficult weather. The impact of this shock to Red Sea transit is already showing up in prices, with data from London-based consultancy Drewry showing container shipping costs leaping 60% over the last week, and up 173% since November (see below).

Supply chains a major inflation risk factor

The fact that carriers have decided to reroute ships suggests they don’t expect a quick resolution to the issue. Bank of America analysts shed further light on the situation, noting that it’s not just attacks in the Red Sea contributing to an increase in shipping costs. Another critical global trade chokepoint, the Panama Canal, has recently seen record-setting drought, leading authorities to reduce the number of ships transiting in the interest of water conservation. After a cut to the number of ships permitted to pass, from up to 36/day to 22/day, auctions of “fast passes” for ships waiting in the queue have led to surging tolls; one operator reportedly paid a one-off fee of nearly US$4 million in November to get its ship through. BofA estimates the Panama and Suez Canals represent 8% and 28% of global container volume, respectively, suggesting how far-reaching the consequences of prolonged disruption could be. Closure of the Suez, alone, according to the bank’s analysis, might add 30% to transit distances for tankers and bulkers, and add 1-2% to fleet demand. All of this will show up in prices, as freight rates surge, origin-destination spreads gap out, and fuel costs rise. Although the current situation still pales in comparison to pandemic-era shipping pain (see above), investors should keep an eye on this and other geopolitical shocks as major risk factors in the path to further disinflation and much-desired rate cuts.

You are now leaving Rayliant.com

The following link may contain information concerning investments, products or other information.

PROCEED