Politicizing the inevitable increase in America’s national debt

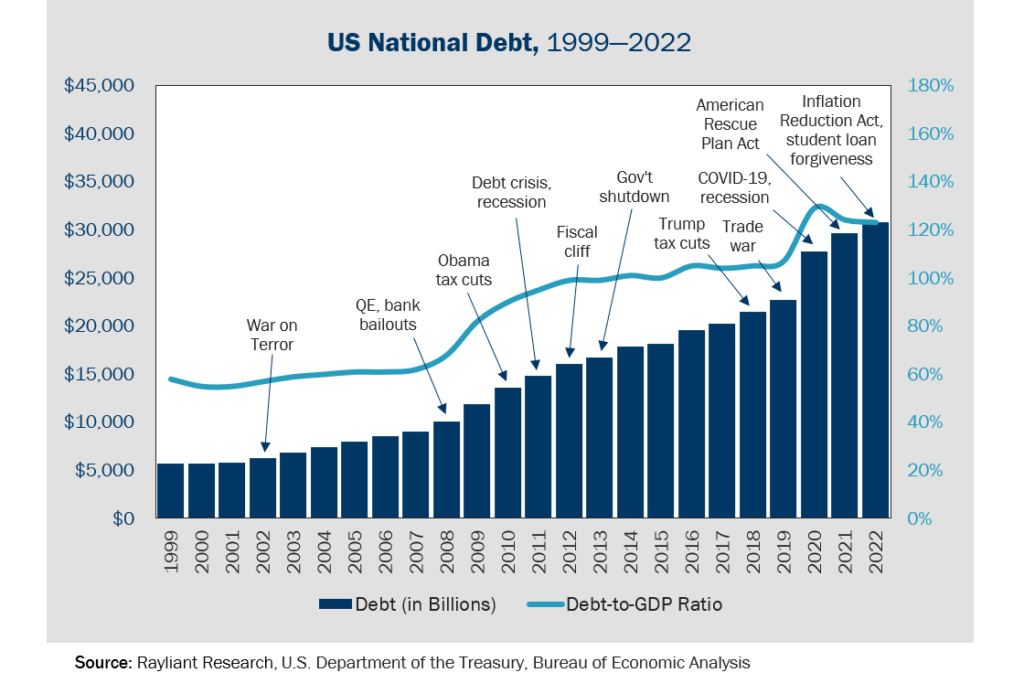

Here we are again: The US government is pushing dangerously close to the debt ceiling, that perennially increasing upper bound imposed by Congress on the nation’s capacity to spend itself deeper into the hole. By the end of 2022, the US national debt had swelled to over $31 trillion, amounting to over 123% of the country’s GDP (see below), with an average annual budget deficit of around $1 trillion since 2001 forcing Congress to occasionally vote on raising the limit. The most recent vote to bump up the debt ceiling was in 2021, though there have been a grand total of 78 increases since 1960. According to the Council on Foreign Relations, 49 of those came under Republican presidents, and 29 under Democrats. Despite both parties overseeing the steady rise in US borrowing, debt ceiling mechanics have become much more politicized within the last fifteen years, with officials on both sides of the aisle playing a game of chicken as the US hurtles toward default.

Showdown creates risk of a “constitutional crisis”

According to a study by the World Bank, when debt-to-GDP exceeds 77% for an extended period of time—the US breached this level in 2009, paying to fix the Global Financial Crisis—sustained economic growth is likely to suffer, with every percentage point of debt above this level estimated to cost an economy just around 2 bps of growth per year. But it’s not the long-term problem of high debt levels making investors especially anxious these days: rather, the debt ceiling is giving investors jitters because of what a protracted stalemate might do to the nation’s credit. Last week, US Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen warned of a constitutional crisis that risks economic and financial catastrophe if Congress does not raise the federal debt limit within weeks. Analysts have circled June 1st as the first day government could run out of cash.

Gauging the economic risk of an impasse

What would some of the consequences be? On the economic front, the Brookings Institution, a Washington think-tank, argues that even a short-lived impasse will cause completely avoidable long-term damage to the economy. Economists at Moody’s warn that two millions jobs could be lost in such a scenario. If the US ends up in a drawn-out default scenario, the White House Council of Economic Advisers predicts a severe recession comparable in magnitude to that experienced amidst the Global Financial Crisis of 2007-08. The tendency toward brinksmanship around the debt ceiling has already done considerable damage, with particularly nasty squabbling in 2011 leading to an S&P Global Ratings downgrade and an estimated $1.3 billion of additional borrowing costs for the year, according to the Government Accountability Office.

Our bet: History will repeat

Ultimately, we see this year’s sparring as another game of chicken between Dems and the GOP, exacerbated somewhat given our proximity to the presidential election cycle. A standoff will likely continue until just before the government runs out of money—in 2011, the Treasury was within 2 days of draining its account before a resolution on the matter—and the leadup to a deal will be full of anxiety for investors. In financial markets, anxiety translates to volatility, and the stress is already apparent. The MOVE Index, for example, a measure of bond market turbulence similar to the VIX for equities, currently sits around 67% above its 10-year average, and Treasury yields at the front end of the curve, most vulnerable to a US default, have jumped in recent days. We expect more volatility and further short-term pain for investors as a deadline for raising the debt ceiling nears, though such turmoil could create a good entry point as fear takes hold and spreads widen.

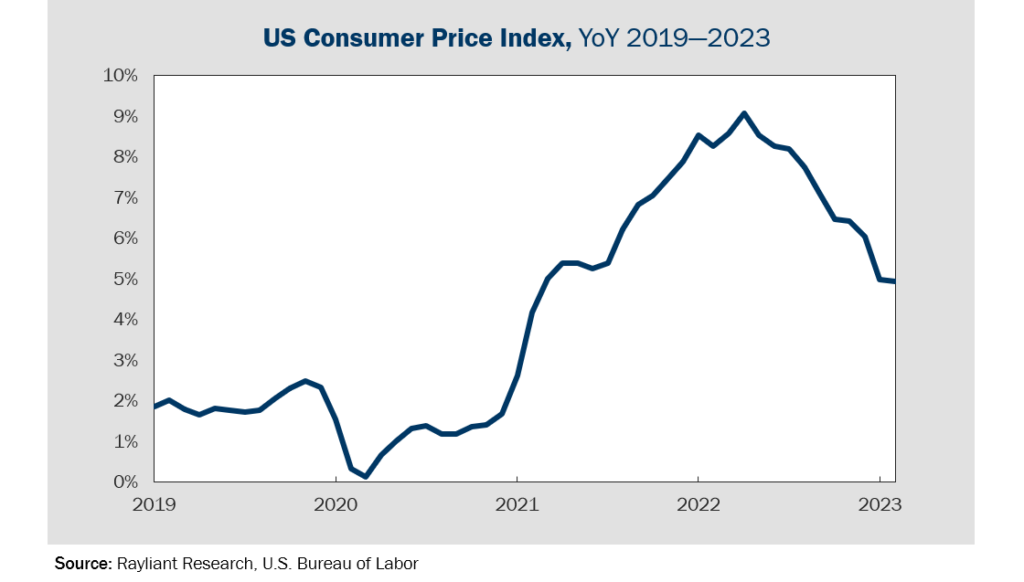

Fed pause much more likely after soft April CPI

The good news for investors is that last week’s inflation data makes the prospect for a pause in hikes this June considerably stronger. Consumer prices increased at their slowest pace in two years in April, according to the latest CPI reading. Headline inflation rose 0.4% over the last month, marking a year-over-year increase of 4.9% through April. That was less than analysts had been forecasting and down from a 5.0% annual increase in March. Now, with ten months of consistent headline inflation declines under our belt (see below), central bankers will have an easier time justifying a pause at June’s gathering of the FOMC. Stress felt by the banking sector gives the Fed all the more reason to take a breather from hikes and let last year’s aggressive tightening continue working its way through the system before putting in additional rate increases. In the weeks ahead, any evidence of easing supply pressures or weakening demand growth will help buttress the case for a pause in June. Traders apparently agree; after reflecting a 78% chance of Powell pausing prior to the April CPI release, markets now put the likelihood of a pause at the June meeting at 97%, according to CME data.

For a pivot, doves may need to wait a little longer

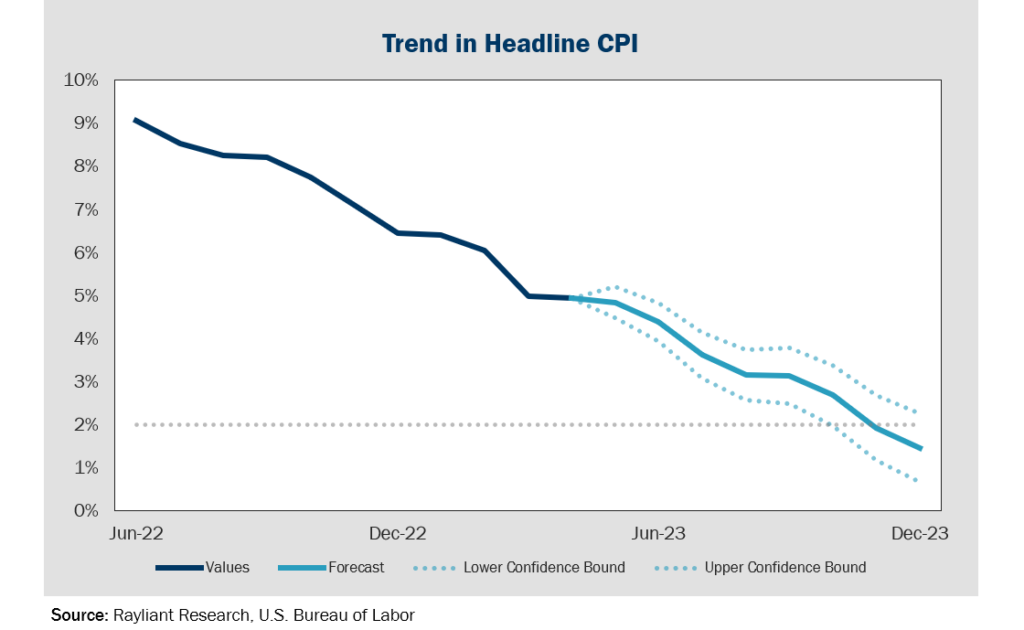

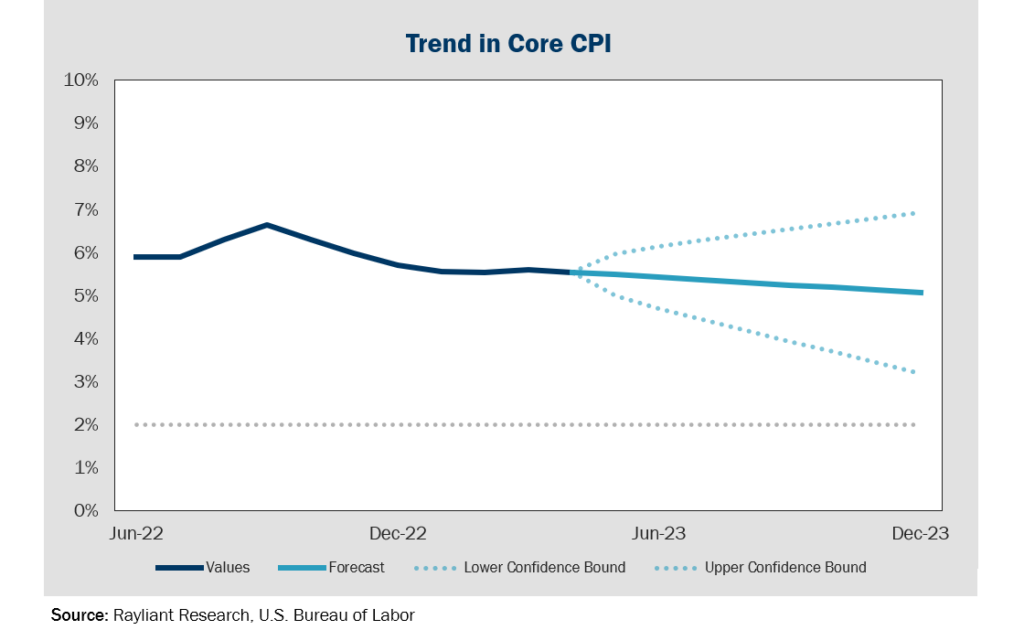

Despite feeling better about the likelihood of a break in super-hawkish Fed policy, we believe the market remains overly bullish on the prospect of easing. The trend in headline CPI is promising, to be sure, with a simple extrapolation putting inflation below the Fed’s 2% target near the end of 2023 (see first chart below). Unfortunately, a view of core CPI (second chart below), which strips out volatile food and energy prices, is more sobering. Looking at the core of inflation reveals a stickier rise in prices that’s trending down, but nowhere near fast enough for the Fed to be comfortable with cuts by the end of this year. While in the short run, the market may cheer a June pause, we see much less room for an upside surprise than for a downside shock.

Disappointment could come in many forms, from an unlikely (but still possible) 25 bps hike in June, to hawkish messaging around that meeting, or even economic data showing the tightening that got us this far in the Fed’s fight against inflation has done more damage than investors are currently pricing in. The upshot is that we remain rather cautious on equities and longer-duration bonds.

Growing addiction to chips raises national security concerns

Analysts at market research firm TrendForce estimate the artificial intelligence underlying OpenAI’s ChatGPT made use of around 20,000 Nvidia graphical processing units (GPUs). That’s a lot of chips. But of course, these days it’s hard to think of anything useful that doesn’t have a microprocessor: from cell phones to televisions, cars to household appliances. In the last few decades, the world has become much more dependent on semiconductors to power personal devices, vehicles, and smart homes. That’s been great for consumers and the companies supplying them. But there’s a downside to our reliance on chips, which came into focus amidst shortages arising during the pandemic, leading to extensive backlogs and blistering inflation. Although semiconductors originated in US research labs, the vast majority of chips manufactured today are produced outside the US, making supply chain issues in the space a potential national security concern.

Increasing global competition among chipmakers

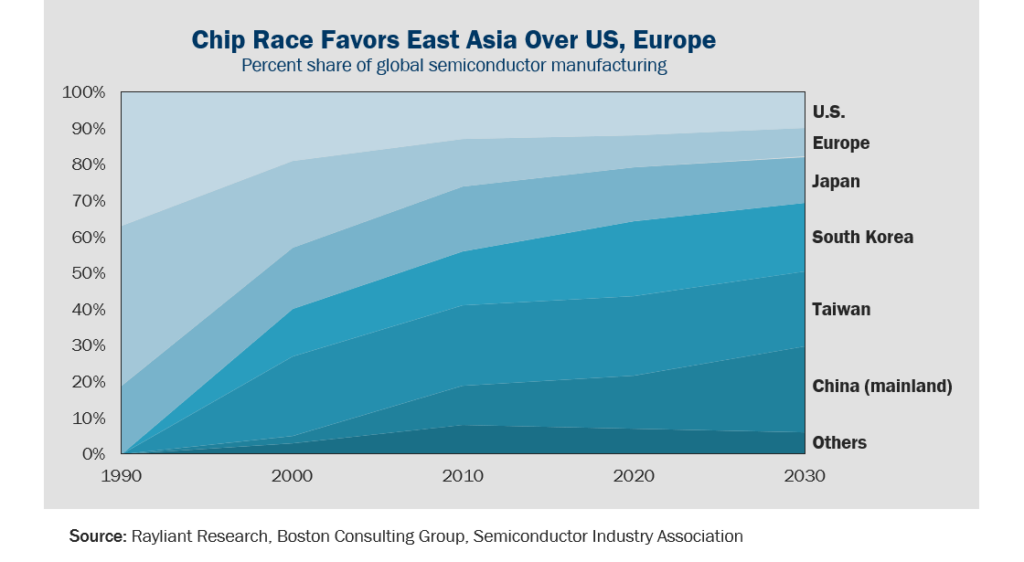

Underscoring the geopolitical risks involved in semiconductor supply is that fact that chipmaking is truly a global business. High demand for semiconductors has attracted many players to field, with a handful of major economies growing to significant market share in the 50 years since Intel put out its first commercial microprocessor. While Taiwan, South Korea, Japan, the US, and China have long dominated, a longer list of countries has more recently developed significant production know-how and entered the fray, including the likes of Israel, the Netherlands, Malaysia, the UK, and Germany. Over the last few decades, one clear trend has been a decline of US and European chipmaking in favor of East Asian manufacturing, as illustrated below.

Taiwan has probably been the most successful in cementing its place at the top of the industry, benefiting from a robust end-to-end semiconductor supply chain, spanning basic R&D—developing the IP underlying increasingly sophisticated designs—to fabrication, manufacturing, and testing for quality control. Indeed, so sophisticated is Taiwan’s infrastructure that some chips can’t be made anywhere else. Meanwhile, China has been building out its own semiconductor production capacity, driven by policy that has only accelerated in recent years as the world’s largest market for semiconductors also suffered under COVID-related supply shortages. Escalating technological competition with the US and a recognition that America and its allies have a stranglehold on global production of the most complex semiconductors have led Chinese authorities to prioritize support for the domestic chipmaking industry as a crucial pillar of national security policy. Boston Consulting Group expects that trend will bring Chinese production to a quarter of the world’s supply by the end of this decade.

CHIPs should help US manufacturers to reverse course

Naturally, US policymakers are aware of both China’s chipmaking ambitions and the long trend toward offshoring semiconductor manufacturing. Today, while the US accounts for 46% of semiconductor sales, it only possesses 12% of global manufacturing capacity. When one considers robust increases in semiconductor demand against the backdrop of a decades-long reliance on foreign companies for chip production, it’s understandable that the same lawmakers fighting over whether or not to let the US default on its debt are still capable of seeing eye-to-eye on the need for dealing with risks to America’s chip supply. The legislative push has already begun and is gaining traction, with the CHIPS and Science Act of 2022 extending $52.7 billion in direct funding and tax incentives for the research and development of semiconductors. The US Senate described this program as “critical to the economic growth and national security of the United States.” Meanwhile, America’s diplomatic machine is hard at work imposing pressure on US chipmakers’ competitors and securing an edge for domestic manufacturers through work with America’s allies. We see these trends as offering great support for firms in the US semiconductor industry—particularly those with a strong footprint in R&D—making us quite bullish on select stocks in the sector over the next few years.

You are now leaving Rayliant.com

The following link may contain information concerning investments, products or other information.

PROCEED