Flows into bonds underscore allure of yields

The steep rise in US interest rates over the past 12 months, as the Fed pushed its policy rate up by five percentage points, has Treasury note yields higher than they’ve been in over a decade. Now, with the US central bank set for a pause, signaling at least the possibility we’re at the end of this tightening cycle, both institutional and retail investors have been rushing to lock in high yields on sovereign and corporate bonds. That marks a notable shift in investors’ asset allocations from just a few months ago. During last year’s bond rout—the Bloomberg US Aggregate Bond Index dropped -13% in 2022—Morningstar data show $330 billion flowing out of active fixed-income funds in the US. This year, the tide has turned, with more than $100 billion pouring back in since the beginning of January. Investors clamoring to buy Treasuries is reflected in the rapid drop in bank deposits in recent months, which played a big part in the March bank crisis. Professional money managers have also been making a shift, according to Bank of America, whose monthly survey of global asset managers saw bond allocations at their highest level since 2009.

But beware the rising stock-bond correlation

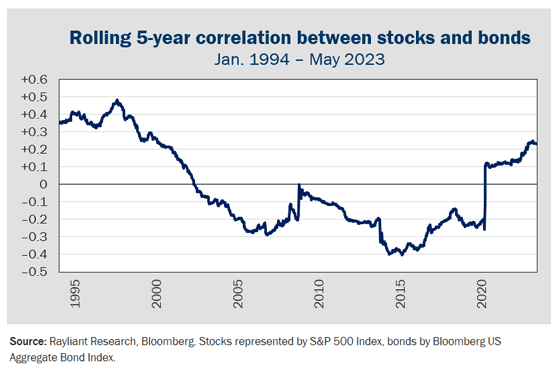

Naturally, the promise of yield in bonds for the first time in a long time has tempted risk-averse investors, including those managing retirement savings, to make even bigger allocations to fixed income. Of course, shifting weight from stocks to bonds when the equity risk premium is low seems like a sensible move, though a word of caution is in order for investors who imagine they’re also enhancing their portfolio’s diversification by better balancing their allocation between stocks and bonds. While the correlation between stocks and bonds has been reliably negative for most of the last two decades—making a 60/40 portfolio very effective in its diversification—the comovement of stocks and bonds has jumped since the pandemic and, while still low enough to provide meaningful diversification benefit, is decidedly positive and seems to be steadily rising (see below). This was painfully apparent to investors in the 60/40 portfolio last year, which posted losses of around -18% in 2022, as both stocks and bonds suffered significant losses. In fact, a higher correlation between equity and fixed income performance is often observed during periods of macroeconomic change, especially in times of heightened inflation uncertainty. While we see an increase in yields as great for investors, we also expect higher volatility in bond returns going forward and somewhat less benefit from bonds as a diversifier relative to equities in the medium-term.

Traders finally backing our bet on ‘higher for longer’

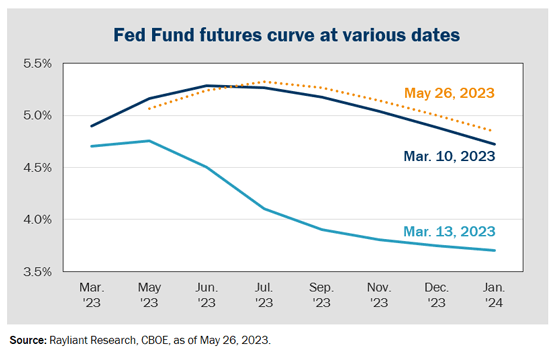

While flows into fixed income have been positive, traders within the bond market have significantly changed their positioning since mid-March, when the collapse of Silicon Valley Bank (SVB) triggered a big shift in interest rate expectations. At that time, we took what turned out to be a contrarian view on the outlook for Fed policy, projecting rates to remain high for some time in the face of sticky inflation and a robust US economy, with financial sector turmoil marking a fairly contained symptom of the Fed’s resolve as opposed to a prompt for rapid easing. In the last two months, events have played out in line with our thesis: Concerns over the banking crisis faded, inflation remained persistent, the US economy sustained its strength, and the Fed continued pushing a relatively hawkish message. Futures prices have reacted to these developments, moving to reflect expectations of a later move to easing. While traders still anticipate rate cuts by the end of this year, they’re now not seen beginning until late in the second half. Moreover, the expected pace of easing has diminished, with implied forecasts of two cuts by the end of 2023, bringing the Fed’s policy rate to just around 4.7% (see below).

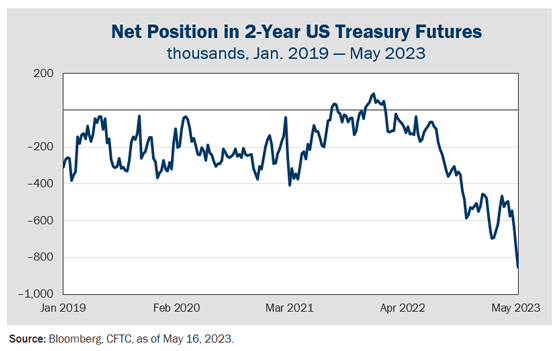

Futures data from the CFTC reveal even more sophisticated bets being placed by fund managers with a view on the trajectory of Fed policy that aligns closely with hours: namely, that sticky inflation and a strong economy will keep the US central bank on its tightening path for some time to come, putting more upward pressure on yields further out the curve. This expected steepening of the yield curve is reflected in record short positions in two- and five-year Treasury futures—bets that prices on those notes will fall, sending yields higher (see below). Resolution of the debt ceiling drama represents another potential shock to the yield market, as issuance by the Treasury to the tune of US$1 trillion over the next six months after the ceiling is lifted would suck up liquidity and likely send prices lower.

Inflation isn’t coming down fast enough to warrant cuts

Given we remain more bearish than consensus, although we’ve correctly called Fed policy thus far, it’s always worth asking: Where could our story go wrong? An obvious explanation for the market’s forecast of rate cuts by year end is that inflation could come down faster than economists predict, giving the Fed enough comfort to start easing sooner. Based on the trajectory of rising prices, while we’re encouraged by the trend in inflation, in our view it’s just not happening fast enough. Last Friday, the US Bureau of Economic Analysis delivered another data point in support of that view, as April PCE inflation notched a 0.4% increase from March, representing 4.4% year-over-year inflation, versus expectations for a reading of 3.9% (core PCE came in at 4.7% year-over-year, also higher than economists’ forecast of 4.6%). At this pace of decline, with stop-and-start softening, it’s hard to see the Fed feeling fit to lower rates. Moreover, with economic activity slowing—the US ISM Manufacturing PMI, for example, ended April in contraction territory and just off a 3-year low—the combination of hot prices and cooling economic activity makes dreaded ‘stagflation’ a real threat.

Could financial stress speed inflation’s decline?

So, if rising prices aren’t responding fast enough to Fed policy on their own, could emerging financial stress—think SVB, Signature, Credit Suisse, and First Republic—help to accelerate inflation’s decline? A recent study performed by economists at the Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City sought to put numbers to that question, investigating how effective financial stress is in reducing inflation. The authors of the study showed that a one-standard-deviation increase in financial stress would likely lead to a 0.70% rise in unemployment and only a 0.4% drop in CPI inflation within one year of the shock. That suggests the financial crisis would have to be quite deep, indeed, for economic damage to spur disinflation sufficient to bring us back down to within the Fed’s comfort zone. Interestingly, the researchers found monetary policy tightening, by contrast, to be a stronger tool in the fight against inflation, with hikes producing roughly the same hit to employment pushing inflation down by 0.65% in the first year after a policy change. Unless the Fed breaks something very badly, we continue to put our money on policymakers applying higher-for-longer hawkishness as a more effective lever in the fight against inflation.

You are now leaving Rayliant.com

The following link may contain information concerning investments, products or other information.

PROCEED