June inflation comes in surprisingly soft

Last Wednesday, the US Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) reported the last really big piece of data before the Fed’s July FOMC meeting, the June CPI. Coming in at just a 0.2% increase, month-over-month, 0.1% less than what economists were forecasting, and the lowest annualized rate we’ve seen since March 2021—just 3% versus last month’s 4%. That news played straight into bulls’ narrative: inflation is effectively vanquished and we’re ready for an end to this tightening cycle. Stocks and Treasuries rallied, while the dollar slid lower. Meanwhile, we’ve been keeping an eye on futures markets, and we noted that the expectation implied there for a 25 bps hike in July went from 93% at the beginning of last week to almost 97% by Friday. So, what was it about June inflation that would fail to impress the Fed and keep us on a path to higher policy rates by the end of the summer?

Fed will still see core CPI as way too hot

For one thing, headline inflation doesn’t tell the whole story. Indeed, one of the reasons CPI has been coming down so fast in 2023 is that grocery and gasoline prices have been receding. That’s great news to households, of course, so we shouldn’t discount this development too much, but those volatile food and energy prices can obscure stickier trends in CPI. And while it’s true that core inflation, which strips out food and energy, also rose less than expected—0.2% month-over-month, versus forecasts for a 0.3% increase—the year-over-year number is still at 4.8%, which is way higher than the 2% central bankers want to see before declaring victory on rising prices.

Inflation likely to bounce back in July

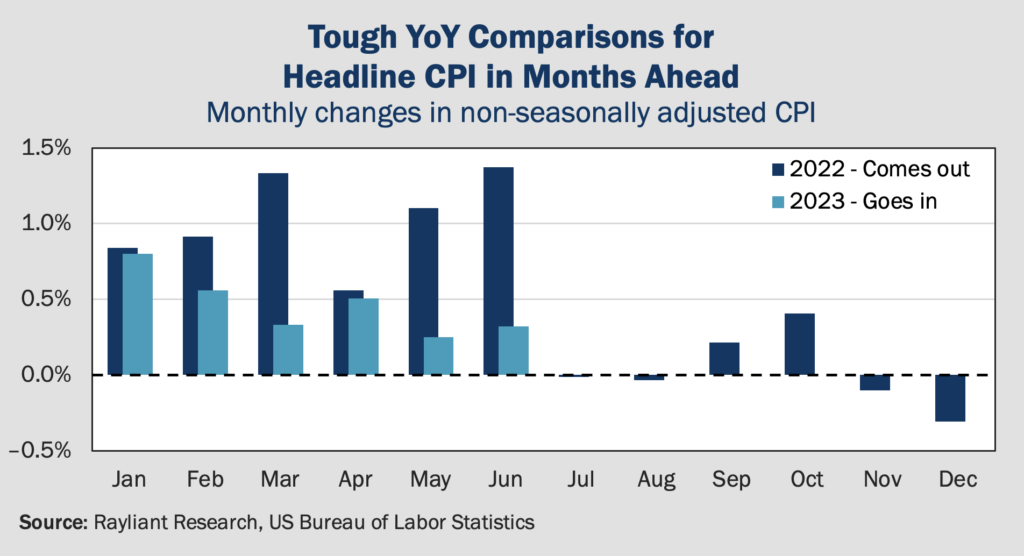

There’s another more technical reason to curb our excitement and expect some reversion on June’s gains next month: the so-called ‘base effects’, which relate to the point of comparison in those year-over-year calculations of inflation we’re constantly seeing quoted. Around this time in 2022, the CPI hit a crescendo. The monthly increase in headline inflation last May was 1.0%, while the monthly rise in prices for June 2022 hit a whopping 1.4%. When such big jumps roll out of year-over-year inflation calculations, it’s easy to show annual gains, even if the most recent numbers don’t make the Fed happy in absolute terms. Seeing a 1.4% increase in June 2022 replaced by a 0.2% increase in June 2023, of course things look better. Now we’re facing the opposite scenario, given a July 2022 monthly change of just below zero. Unless next month’s CPI comes in at zero or negative, base effects dictate inflation will bounce back on the next print as a blank falls out of the calculation. In that regard, the next six months will be challenging—especially with some negative month-over-month numbers lurking from last November and December (see below).

Investors right to be concerned about China’s economy

Inflation remains higher than usual in the US, but China has the opposite problem. The world’s second-largest economy saw CPI flat in June, while factory-gate prices fell further, fueling concerns about the risk of deflation and increasing calls for big-time stimulus. Part of China’s problem is out of its direct control. Weakening overseas demand as large economies slow down, combined with supply chain migration trends on the back of heightened interest in onshoring and friend-shoring have adversely affected the country’s trade outlook. Domestically, youth unemployment has reached a troubling high of over 20%, while property market prospects continue to disappoint, with some estimates suggesting that developer debt equivalent to 12% of GDP is at risk of default. Notwithstanding a reasonably smooth trip by US Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen earlier this month, well-publicized frictions with the US have made foreign investors uneasy, regardless of macro gloom and doom. But even those who elect to sidestep a direct investment in China given the economic uncertainty should probably be hoping the picture brightens, as China’s growth could be critical in mitigating a potential recession in Europe and the US.

China’s biggest problem is a lack of confidence

As we’ve mentioned before, we see the primary issue holding back China’s economic recovery as painfully low domestic sentiment on the part of consumers and companies. Households are unwilling to spend down their pandemic savings with so little confidence on income and employment, while Chinese companies are unlikely to resume investing until they observe a sustained demand recovery, which poses concerns for China’s private sector, accounting for 80% of urban employment and generating nine out of every ten new jobs. The obvious catalyst to improve sentiment on both fronts is a major stimulus package from Beijing, but so far in this cycle, measures to support the economy have been limited.

Can investors bank on more fiscal stimulus?

To date, the level of stimulus has been decidedly disappointing. The People’s Bank of China made cuts to key policy rates last month, but that easing was measured and makes little difference with the underlying demand for loans so weak. Fiscal policy support is much more important, but we’ve seen too little of that, as well. Make no mistake, however: this is the area to watch in the weeks ahead, and there are reasons to be hopeful. Tax breaks on EVs have already been announced, along with incentives for green technology companies. What we want—and expect—to see next is a roll-out of more meaningful support for the property sector, which will do more to boost confidence on the part of consumers and companies throughout that massive segment of China’s economy. We were also encouraged by the US$985 million fine recently leveled at Alibaba’s Ant Financial, which we actually view as an olive branch extended to big tech, clearing the way for China’s platform companies to once again add to the country’s growth. Given how low valuations in China have sunk, with forward P/E for the onshore CSI 300 Index falling to 12x, a big fiscal package could deliver solid gains to investors willing to allocate amidst such bleak stats.

EM priced right at a good spot in the cycle

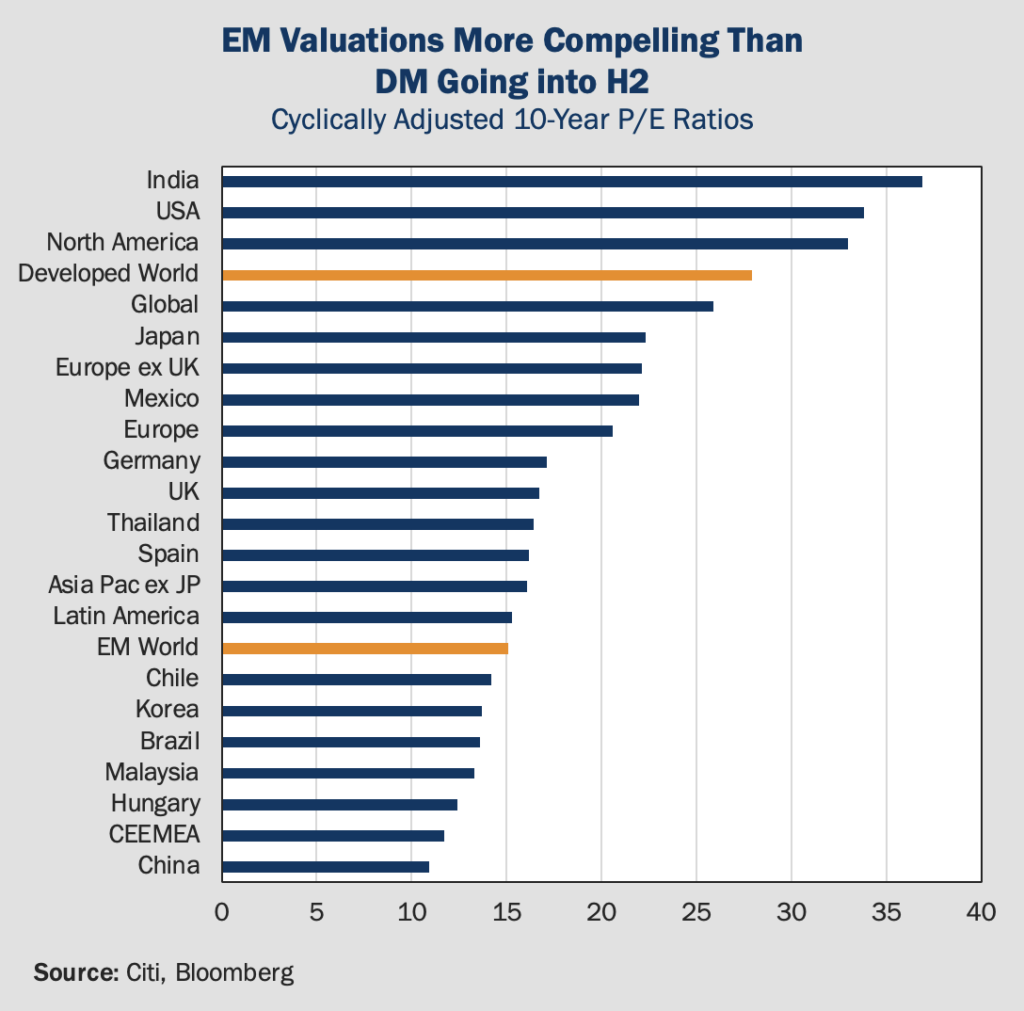

China tends to suck the air out of the room in most conversations about emerging markets—it does represent up to one-third of broad EM indices—but there’s much more to EM that merits investors’ attention. For one thing, China isn’t the only apparent bargain among emerging economies on valuation. Judging by cyclically adjusted P/E ratios, while the US and other developed markets look quite expensive, emerging markets rank as a clear value play (see below).

That comparison is more interesting when one considers the macroeconomic context. While tightening across developed economies continues in a battle against persistently rising prices, threatening a significant downturn in Western economies, policymakers in emerging markets were generally ahead of the curve in fighting inflation, sooner to raise rates and now in a position to pivot earlier to easing. This dynamic partly explains why EM bonds have done so well in 2023. The JPMorgan benchmark for local currency government bonds in emerging markets, for example, has delivered a total return of 7.5% year to date, with the Latin American sub-index posting a remarkable 21% over that period. Amidst a risk-on frenzy in developed market stocks, particularly the US, we think there’s a strong case to be made that EM equities have lagged behind in pricing a comparatively favorable macro picture.

China’s troubles a tailwind for EM rivals

From another angle, the very challenges plaguing China present big opportunities for investors in the EM ex-China basket. One such obstacle to China’s continued growth is the oft-cited “decoupling” of the world’s two largest economies against a backdrop of geopolitical conflict encompassing everything from trade and technology to social issues and national security. But not everyone sees this is a problem. Nearshoring has been a boon for America’s southern neighbor, with profound changes taking place in US-Mexico trading patterns. After China’s admission to the WTO in 2001, Mexico’s trade with the US declined significantly as American companies quickly took advantage of cheap Chinese exports. Now, with the introduction of tariffs during the US-China trade war, pandemic-era disruptions to logistics and—increasingly—concerns over supply chain security, Mexico has made back lost ground, surpassing China as largest trading partner to the US for the first time in two decades in the first four months of 2023. Other countries like South Korea, Taiwan, and even up-and-coming India are vying to make gains at China’s expense as geopolitical factors push major economies to quickly diversify trading ties.

EM investing still not a walk in the park

Even with such tailwinds, investing in EM has its pitfalls. India is a good case study there, in part because it has been a very popular destination outside China for foreign flows into EM, pushing it to much higher valuations in 2023. On the back of that good run, Indian stocks sat conspicuously atop the valuation chart presented above, coming in even higher than the US market. That makes good deals a little harder to come by these days and creates a bit less margin for error. While we still see opportunity in India, despite a high P/E, as earnings should grow to catch up with prices, we worry a passive approach of simply plunking cash into the index might not be the best way to capture that. Indeed, investors in the MSCI India index learned that the hard way earlier this year, when the Adani Group—a 5% weight in MSCI’s benchmark—crashed following a short-seller’s allegations of a massive fraud at the firm. The country’s less business-friendly environment caused problems again last week, when Taiwan’s Foxconn pulled out of a US$19 billion chipmaking project in India, which many suspect was a function of low trust and fears about policy stability. Such patches of rough are par for the course in developing economies, which is exactly why we see active management as a better bet on the tactical opportunity EM presents.

You are now leaving Rayliant.com

The following link may contain information concerning investments, products or other information.

PROCEED