Following the dark news coming out of Ukraine over the last two months, our hearts break at the sight of the human tragedy unfolding each day and the grave impact this senseless act of aggression has inflicted on the lives of millions of innocent people. It is a grim part of our work that entails looking at such conflict through the lens of an economist or statistician, and coldly assessing the costs and the risks events like this pose to our clients. Even so, we find that the task reveals hopeful trends and offers useful lessons for global investors who must inevitably cope with such crises in the course of protecting and growing capital over the long term.

For one thing, those of us who have invested through many past cases of geopolitical conflict would likely agree that one of the most notable aspects of the current episode is the extreme degree to which markets have been deployed as financial weapons, forcing Russia and its citizens to internalize the costs of its belligerence. Beyond the old tools of economic sanctions, decades of intense globalization have created an interconnected community of nations, for whom the benefit to remaining a part of the network creates strong incentives not to act so as to be cut out.

In many ways, the public reaction to Russia’s invasion reflects a trend toward ESG investing that has been underway for some time, though we have rarely seen customers and shareholders put such pressure on companies to act in defense of a country under military siege. For their aggression, Russian citizens have been deprived of McDonald’s, Coca Cola, and Starbucks. They won’t have access to new Samsung and Apple smartphones, nor will they receive shipments of Sony and Nintendo gaming consoles. Disney, Sony, and Warner Bros. will stop releasing films in Russia, and Netflix has suspended streaming.

So far, the West’s economic offensive has failed to deter Russian hostility, and on the face of it, such measures may seem weak in comparison to military weapons. It’s worth noting, however, that no amount of spending on national defense can insulate Russia’s population from the loss of so many goods they have come to expect since the end of the Soviet era—let alone protect them from the more direct, widely felt, and extreme costs imposed by traditional sanctions. Bank runs and supermarket fights over sugar will undoubtedly take a toll on Russia’s morale in the longer run. The steep price Russia pays in terms of global financial and economic alienation will, at the very least, serve as a stark warning to other would-be aggressors.

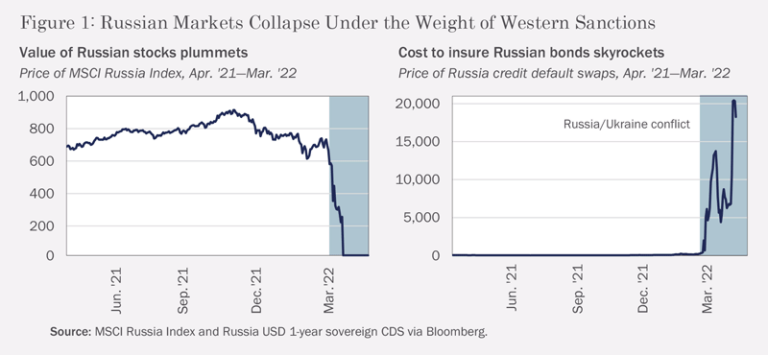

That Russia hasn’t yet called off its attack should not be taken to mean economic penalties haven’t had an effect. Indeed, within weeks of launching its offensive, Russia’s financial markets were already on the brink of collapse (see Figure 1). On 25th February, just one day after Russian stocks lost one-third of their value upon the official start of the invasion, the nation’s stock exchange was shuttered, and global benchmark provider MSCI quickly declared Russian stocks to be ‘uninvestable’, marking positions down to zero. While trading nominally resumed in late March, the longest closure of Russia’s equity market since the fall of the USSR, foreign investors are still barred from transacting. Russian debt hasn’t fared much better, with the price to insure the nation’s bonds against default skyrocketing as sanctions were imposed. Russia officially entered ‘selective default’ in early April, when the country attempted to make interest payments on two dollar-denominated bonds in roubles, the first time Russia defaulted on foreign debt since just after the Bolshevik Revolution in 1917. One obvious lesson for investors is that international diversification remains among the best ways of managing risk and fortifying one’s portfolio against extreme events. Russian stocks and bonds made up a tiny part of global model allocations, limiting prudent investors’ direct exposure to the conflict.

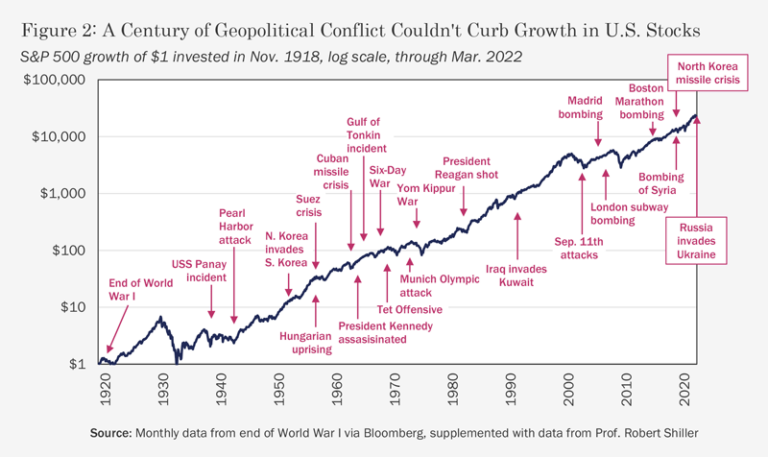

Of course, as the fighting continues, investors will also naturally wonder how the impact might extend to other markets and what the implications might be if the war expands beyond Russia and Ukraine. Here, as is often the case, we believe it’s useful to zoom out and take a broader, data-driven historical perspective on how stocks react to geopolitical events (see Figure 2).

Examining over a century of geopolitical strife since the end of the First World War, we find that the effect on US stocks of international incidents—ranging from terrorist attacks and assassinations to nuclear standoffs and armed conflicts—is typically short-lived, with very few such events even perceptible as stocks have reliably marched upward over the last hundred years.

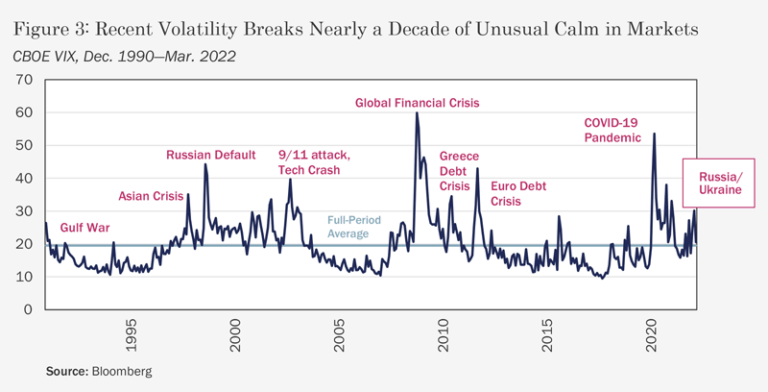

This may come as a surprise, given how salient today’s risk feels when reading the headlines, though we note that the increase in volatility since last year has actually been relatively modest (see Figure 3), and might only seem pronounced because markets have been so unusually calm since the end of the Global Financial Crisis. Ultimately, our experience tells us that the key to navigating periods of market stress, including those induced by military conflict, is separating our very reasonable human response to such events from their actual investment impact on our portfolios, maintaining sensible strategic exposures to risk, and searching for opportunities to add value through disciplined tactical allocations—in other words, the core tenets of our approach to managing clients’ wealth.

Equities

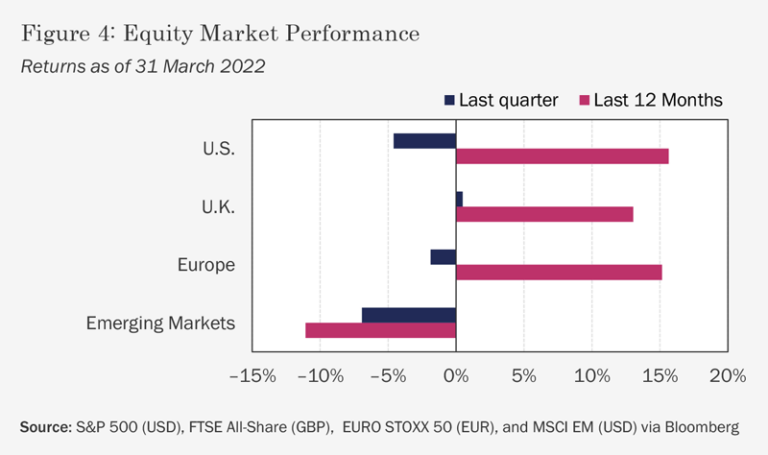

Stocks were weak to start the year, with the S&P 500 experiencing its first correction since COVID hit in early 2020, before rebounding in March to end the quarter off by –4.6% (see Figure 4). Even before Russia invaded Ukraine, fears of monetary tightening weighed on equities, especially growth stocks, whose worth is tied to far-off cash flows, which are more sensitive to rising rates. The Western response to Russia’s attack—ranging from freezing and seizing of oligarch’s assets (not to mention those of the nation’s central bank) to sanctions on Russian oil and its banks being barred from access to the global financial system—stoked fear that global growth might take a more acute hit. Likewise, the shock to commodity prices and supply chains further complicated the work of the Fed, struggling to engineer a ‘soft landing’ for the economy, raising rates to fight inflation without triggering a recession.

Elsewhere in equity markets, European shares slipped by –1.9% in Q1, given their greater exposure to Russian energy (prior to the invasion, Russian oil, gas, and coal accounted for 35%, 55%, and 50% of German imports, respectively), while UK stocks actually posted a modest gain of 0.5% for the quarter, driven by low valuations going into the year, as well as the market’s sector composition: underweight tech, and heavy on energy, mining, and financials, which naturally outperformed in the current climate of geopolitical stress and rising rates. Emerging markets underperformed the broad market, declining by –6.9% for the quarter, not primarily a direct result of the Russian market’s collapse (it was a small part of the index), but more as a product of mounting fears of a global economic slowdown, along with China’s self-inflicted regulatory wounds and its difficulty squaring stubbornly ‘zero-COVID’ policy with the highly contagious variants now locking down Shanghai.

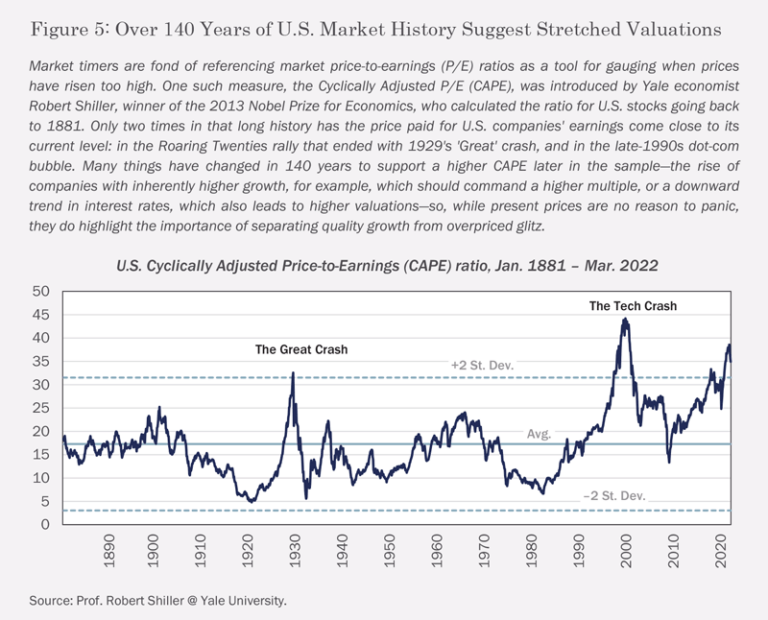

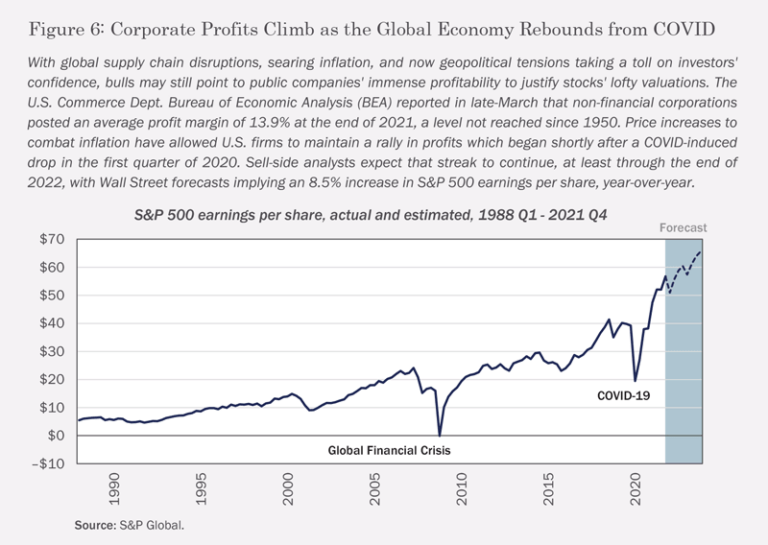

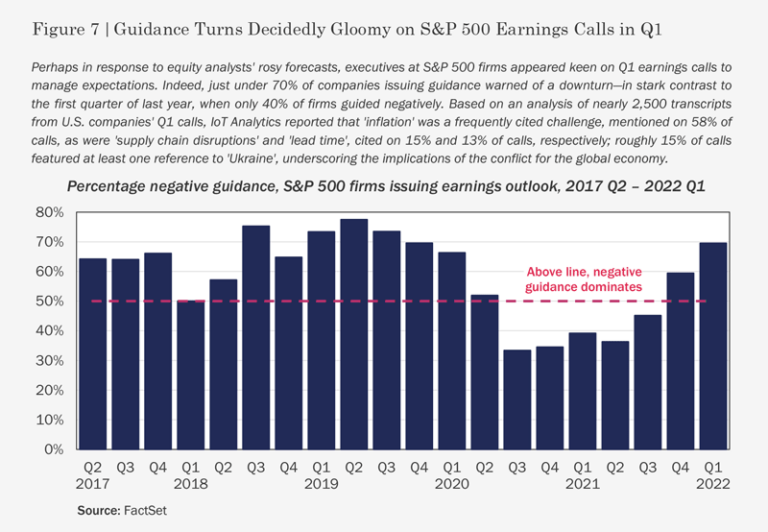

We note that despite their Q1 decline, US stocks still traded at lofty valuations to end March, with the S&P 500’s price clocking in at 35x cyclically adjusted earnings, roughly two times its average since the late 1800s (see Figure 5). While such ratios have a mixed track record as tools for timing the market, they certainly capture the current froth in US shares. We saw more glaring evidence in late March, when Tesla announced a stock split, which practically serves only to make the shares slightly easier to buy for tiny retail investors; the news in fact added $84 billion to the company’s market cap—nearly the entire value of Volkswagen’s stock—in a single day. That said, there are fundamental data to support at least the denominator of the market’s P/E, as corporate profits bounced back strongly from COVID in early 2020, a trend which analysts expect to continue (see Figure 6). Such markets pose risk, to be sure, but also opportunity for active stock pickers, where the challenge becomes separating overpriced ‘growth traps’ from high-quality bargain stocks likely to benefit from a rotation, as excessive optimism gives way to more realistic appraisals (see Figure 7).

Fixed Income

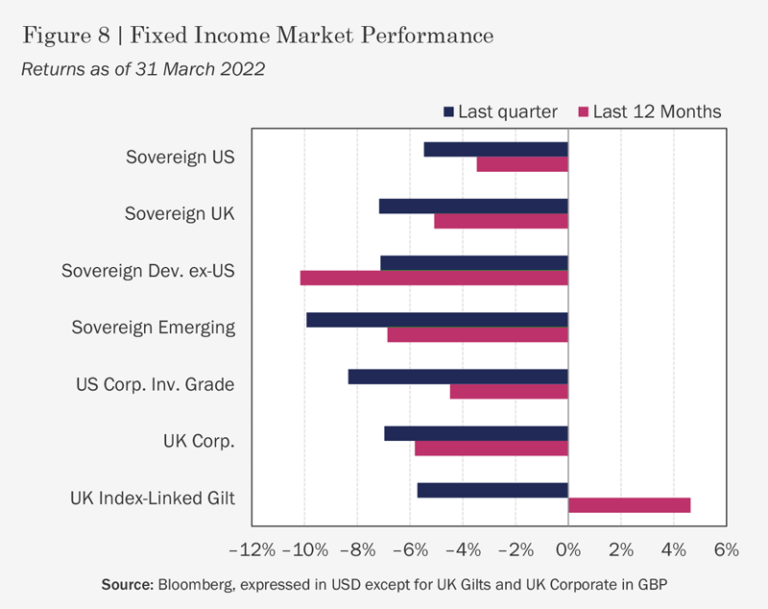

The March FOMC meeting marked ‘lift-off’ for US rates, with a quarter-point hike commencing the Fed’s fight against inflation. Investors anticipated this move, having been pricing in more aggressive action by the central bank to deal with surging inflation over the last few months. The Bank of England, for its part, bumped rates up for the second time in February, and even the ECB—lagging a bit in making its policy pivot—signaled tapering of asset purchases and at least the possibility of rate increases by year end. The inevitable result of this hawkishness, despite a brief ‘flight to quality’ that led Treasuries to rally at the outset of Russian hostilities, was a sharp decline across the board for bonds in Q1 (see Figure 8). Fixed income investors moved to a decidedly ‘risk off’ stance by the end of March, as the geopolitical and macro situation worsened, reflected in rising credit spreads and steeper losses on corporate and EM debt for the quarter.

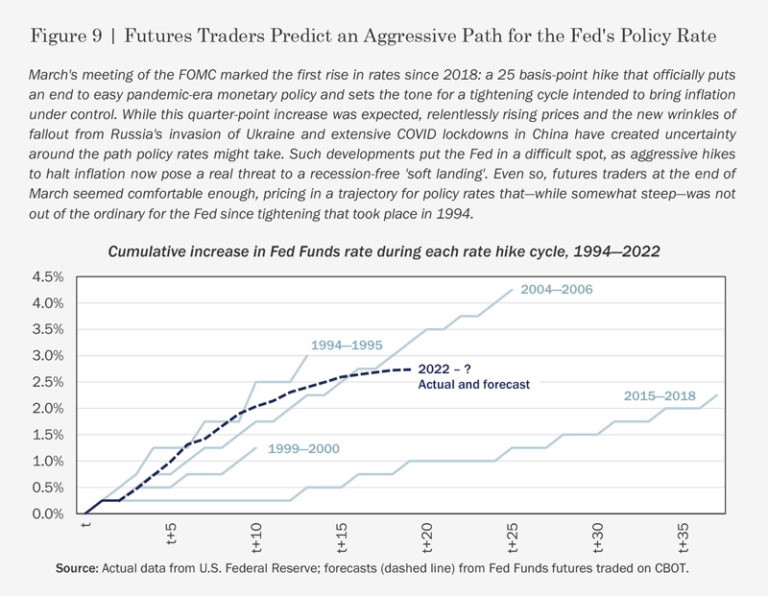

Indeed, between supply chain bottlenecks established in the last year, the emerging crisis in Ukraine, and COVID lockdowns disrupting China’s economy, investors appeared concerned by the end of March that a global recession might be the price to pay for stopping inflation, as the US yield curve inverted: with high rates on the short end due to rising rates in the near term, and lower yields further out, given the likelihood that rates will come back down before long to stimulate a flagging economy. Of course, none of this is lost on central bankers, who walk an increasingly fine line—though, judging by a market-based forecast of the Fed Funds rate’s future path, chairman Powell’s gameplan seems roughly par for the course versus the trajectory of policy rates in past tightening cycles going back three decades (see Figure 9). The silver lining in all of this is that the higher rates climb, the easier it will be for asset owners dependent on investment income to find a halfway decent yield (see Figure 10).

Commodities

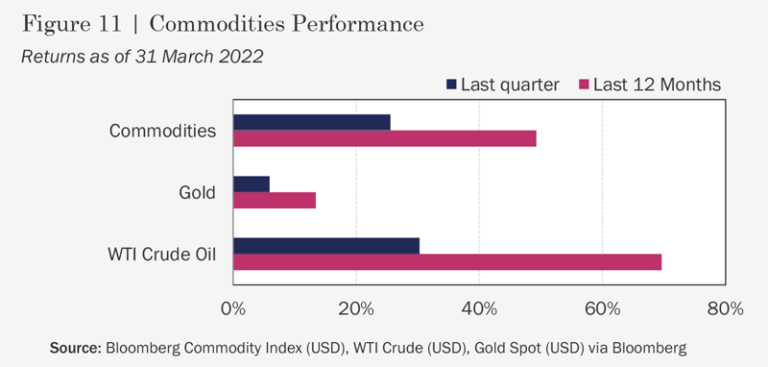

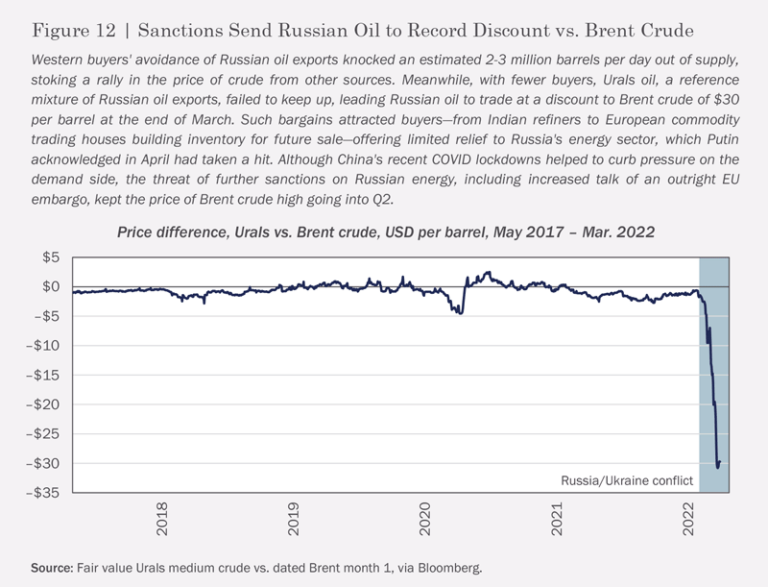

Russia’s attack on Ukraine drove a strong rally in commodities in Q1, with energy and agricultural prices leading the way to a 25.5% gain on the Bloomberg Commodity Index for the quarter (see Figure 11). Prior to the conflict, Russian oil exports made up just about 8% of global petroleum production, with economists estimating the disruption of war and sanctions have removed roughly 2-3 million barrels per day of production, accounting for up to 3% of the world’s supply. With little relief expected from members of OPEC—who have recently stepped up cooperation with Russia—and US shale oil producers finding it difficult to expand capacity in the short run, this shock to supply has kept the price of WTI crude elevated in the wake of Russia’s invasion, which saw prices briefly touch $120 per barrel. The reluctance or inability of buyers to step in and take advantage of a deep discount on Russian oil accounts for a record divergence between Urals and Western crude (see Figure 12).

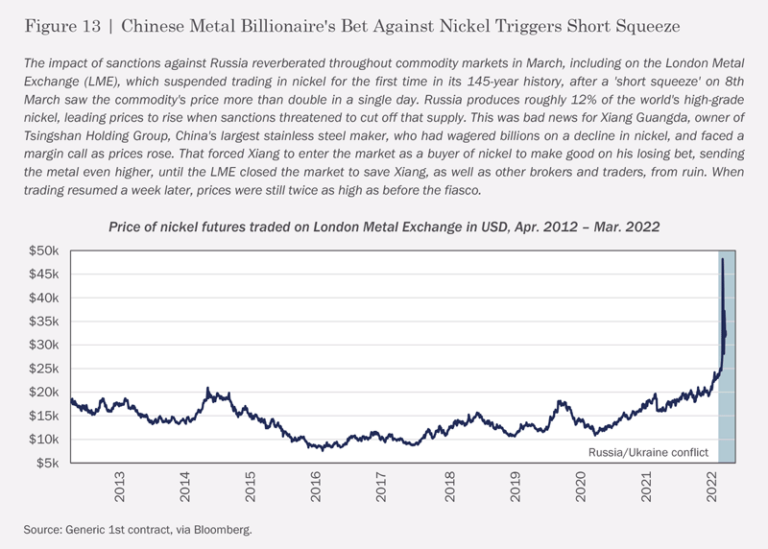

In addition to surging energy prices, the conflict between Russia and Ukraine has pushed up the price of wheat, for which the two nations add up to 30% of global supply. While precious metals posted small gains in Q1, industrial metals recorded larger profits, led by nickel, which gained 54% for the quarter (see Figure 13). The base metal, an important input to lithium-ion batteries, initially rallied in response to sanctions on Russia’s 12% share of global production, before skyrocketing in early March, when a Chinese billionaire’s massive short position was ‘squeezed’, triggering a margin call so severe it forced the London Metal Exchange (LME) to shut trading down for the first time in 145 years. One of the big winners in the episode was Volkswagen, whose hedging operations resulted in the automaker holding one of the largest long nickel positions on the LME and booking a reported $3.8 billion in commodity trading gains as part of its first-quarter earnings.

From the preceding commentary, it will be clear that Russia’s invasion of Ukraine was the driving force behind many investment themes at the start of the year. Entering the second quarter, the big question is whether the fallout from this war—including additional supply chain disruptions and a shock to global energy markets—will ultimately derail central bankers’ attempt to cool off inflation without stalling the world economy. Recent bond market volatility reflects uncertainty on this point, while stock valuations seem to suggest soft-landing optimists may still have the upper hand.

When the fighting in Ukraine began, Bank of America strategists turned bearish and cited a heightened risk of the Fed making a ‘policy error’ that leads to recession; fund managers in a recent survey by the bank put the likelihood of such a mistake—being too late in their response to inflation or tightening too much—at 83%. At this moment, we believe investors are also at greater risk than usual of making errors in their portfolios, as the temptation to radically shift allocations in response to fear can distract from long-term investment plans.

In fact, it is often most profitable to invest precisely when fear is gripping the market. China’s financial policy makers are experienced in this area. For years, the country’s ‘National Team’, an informal name given to a group of state-affiliated financial entities, has sought to prop up China’s stock market during times of stress, engaging in coordinated purchases of struggling shares in beaten-down companies with solid fundamentals. While the motivations for doing so may be superficial and political, the irony is that such a strategy has likely outperformed most market timing fund managers and retail traders.

Given the range of macro and geopolitical perils facing investors as 2022 unfolds, investors inclined to follow this approach should expect more opportunities to ‘buy the dip’ ahead.

Subscribe to receive the latest Rayliant research, product updates, media and events.

Subscribe

Sign upIssued by Rayliant Investment Research d/b/a Rayliant Asset Management (“Rayliant”). Unless stated otherwise, all names, trademarks and logos used in this material are the intellectual property of Rayliant.

This document is for information purposes only. It is not a recommendation to buy or sell any financial instrument and should not be construed as an investment advice. Any securities, sectors or countries mentioned herein are for illustration purposes only. Investments involves risk. The value of your investments may fall as well as rise and you may not get back your initial investment. Performance data quoted represents past performance and is not indicative of future results. While reasonable care has been taken to ensure the accuracy of the information, Rayliant does not give any warranty or representation, expressed or implied, and expressly disclaims liability for any errors and omissions. Information and opinions may be subject to change without notice. Rayliant accepts no liability for any loss, indirect or consequential damages, arising from the use of or reliance on this document.

Hypothetical, back-tested performance results have many inherent limitations. Unlike the results shown in an actual performance record, hypothetical results do not represent actual trading. Also, because these trades have not actually been executed, these results may have under- or over- compensated for the impact, if any, of certain market factors, such as lack of liquidity. Simulated or hypothetical results in general are also subject to the fact that they are designed with the benefit of hindsight. No representation is being made that any account will or is likely to achieve profits or losses similar to those shown. In fact, there are frequently sharp differences between hypothetical performance results and the actual results subsequently achieved by any investment manager.

You are now leaving Rayliant.com

The following link may contain information concerning investments, products or other information.

PROCEED