Even before the recent trade war, the U.S. president had a hand in China’s market, by way of “concept” stocks. They are just one of the quirks found in retail-heavy emerging markets like China, whose inefficiencies—and alpha opportunity—are traced to non-professionals trading as much for entertainment as for profit. In the research below, we investigate the evolution of retail participation in China A shares, the remarkable inefficiencies that creates, and the implications for professional investors.

Al Alvarez’s 1983 book, The Biggest Game in Town, documented the World Series of Poker, a high-stakes tournament played every year in Las Vegas. In the world of equity investing, the same title might just as well apply to China’s mainland stock market. The world’s second-largest market is now valued at over US$7.5 trillion, as of June 2019. Sure, it’s not the biggest in dollar terms, but China’s market does have features that make it an attractive place for investors seeking to ante up for outperformance.

Warren Buffett invoked the card game metaphor in a 1988 letter to Berkshire Hathaway’s shareholders in order to make an important point about success in active management: “Indeed, if you aren’t certain that you understand and can value your business far better than Mr. Market, you don’t belong in the game. As they say in poker, if you’ve been in the game 30 minutes and you don’t know who the patsy is, you’re the patsy.”

“Patsy” is a strong word; it’s probably fairer to think of the distinction as professional versus amateur. In any case, the implication of Mr. Buffett’s comparison still holds true: Like poker, alpha is a zero-sum game. For every winner, there must be a loser. As such, it behooves the intelligent investor to know who’s funding his outperformance.

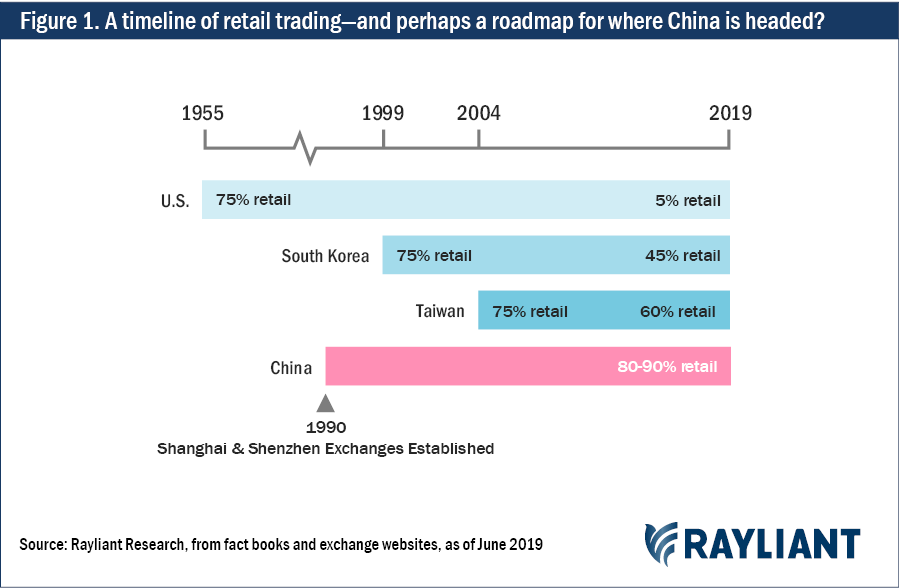

That’s a hard question to answer in the world’s largest market, the U.S., where less than 5% of U.S. stock trading is done by non-professionals. When one takes an active position in a market like that, it’s more likely than not a bet against the smart money. China’s allure is that on its mainland exchanges, the tables are turned, with upward of 80-90% of volume generated by the amateur investors.

Those conditions are especially favorable for quantitative strategies leveraging data to study the behavior of market participants and corporate insiders, as well as the underlying characteristics of firms themselves; these include strategies built to exploit the biased decisions by the non-professionals mentioned above. But to fully appreciate retail trading as a source of alpha in China, it’s worth revisiting how we got here and what that trading looks like.

China’s experience is not unprecedented. It turns out a number of emerging markets have exhibited high retail investor participation early in their history, only to see more professionals enter as these markets have matured, become part of global benchmarks and eased restrictions on foreign ownership. This developmental pattern has been particularly true in East Asia, where perennially high savings rates mean households have ample capital with which to enter the market.

As Figure 1 shows below, even the U.S. was once a retail-dominated market—way back in the 1950s. We don’t think it will take 60 years for China to attract a more professional investor base, but given the experience of South Korea and Taiwan, both of which clock in at roughly 40-60% retail today, it also won’t likely happen overnight. Indeed, if the last few years were any indication, the alpha opportunity in mainland Chinese stocks is only becoming more interesting.

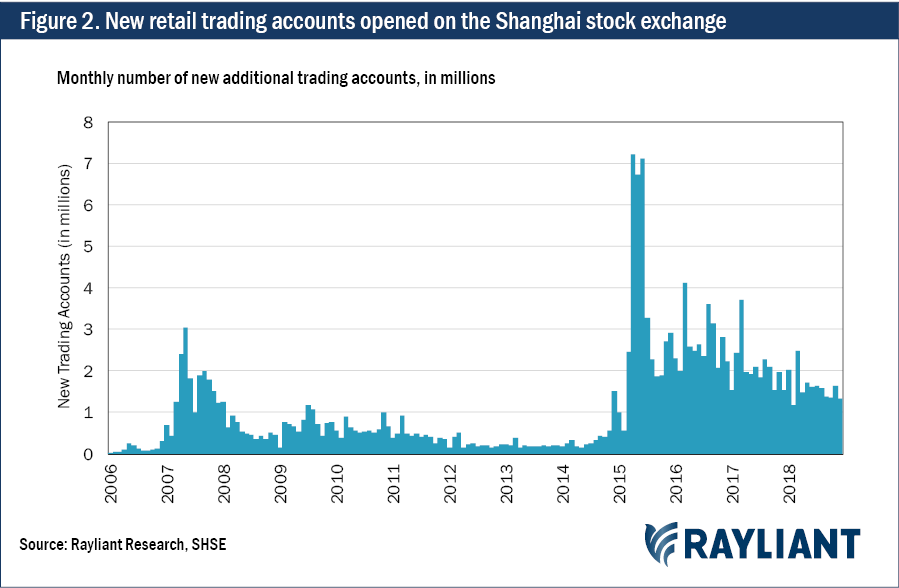

During the late 1990s, in the U.S., it was hard not to hear stories of everyday people striking it rich as amateur day traders. In a market that only went up, everyone looked like an expert—except those who hadn’t yet taken the plunge and set up an account with a discount broker. In such an environment, watching from the sidelines isn’t a pleasant experience. In today’s hyper-connected world, with smart phones and social media blasting nonstop, the “fear of missing out” rises to a whole new level. In China, this dynamic resulted in a massive influx of investors as mainland stocks rallied in 2006-07 and 2014-15.

The three months from April to June 2015 saw roughly 7 million new retail brokerage accounts opened per month in China (see Figure 2). That’s equivalent to every man, woman, and child in the six most populous American cities—or the 21 million people in New York, L.A., Chicago, Houston, Phoenix, and Philadelphia—suddenly diving into the market. A major correction at the end of 2015 put the brakes on that astonishing growth; still, well over 1 million new accounts have been added each month since.3

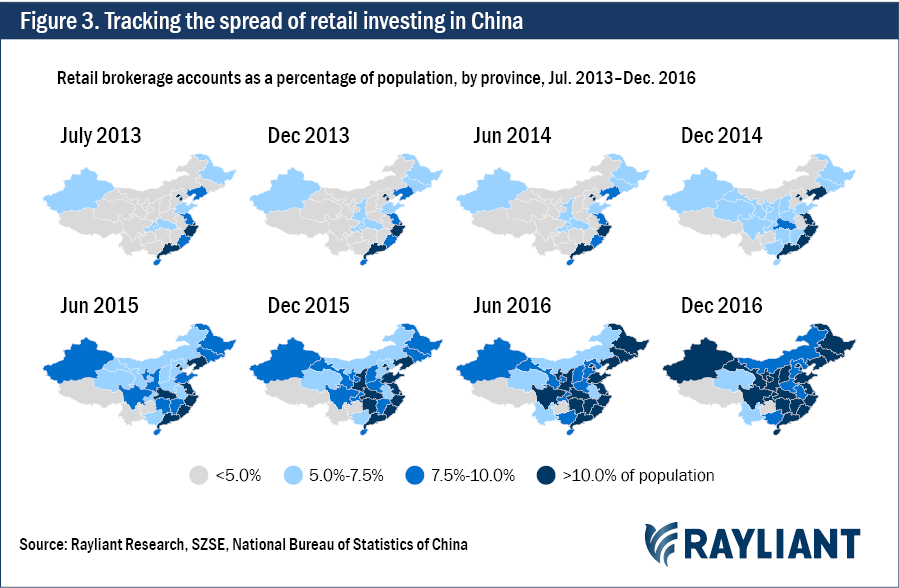

China’s last major market bubble, from 2013 through 2016, offers a lens into the breadth of that retail trading growth (see Figure 3). In just a few years, mainland equities’ surge in popularity among retail investors spread from coastal cities and major commercial centers to some of the nation’s least financially developed provinces, in a pattern mirroring that of an epidemic. Nevertheless, only around 15% of China’s population was in the market by the end of 2018.

So we’ve established retail trading is a prominent feature of emerging markets, not least in China, where tens of thousands of new amateurs enter the game each day. But what do we know about how they trade? One unusual trend, that of the concept stock (概念股 “gàiniàn gǔ”), nicely illustrates how Chinese retail investors often drive prices away from fundamentals, creating many of the opportunities for professionals alluded to earlier.

A concept stock is one favored by Chinese investors not due to strong fundamentals or thorough analysis, but rather because the shares adhere to some pattern or theme. These stocks are often chosen on the basis of nothing more than the company’s name—a strategy we might call “investment-by-pun”. Sound strange? Let’s consider an example and see how weird things get.

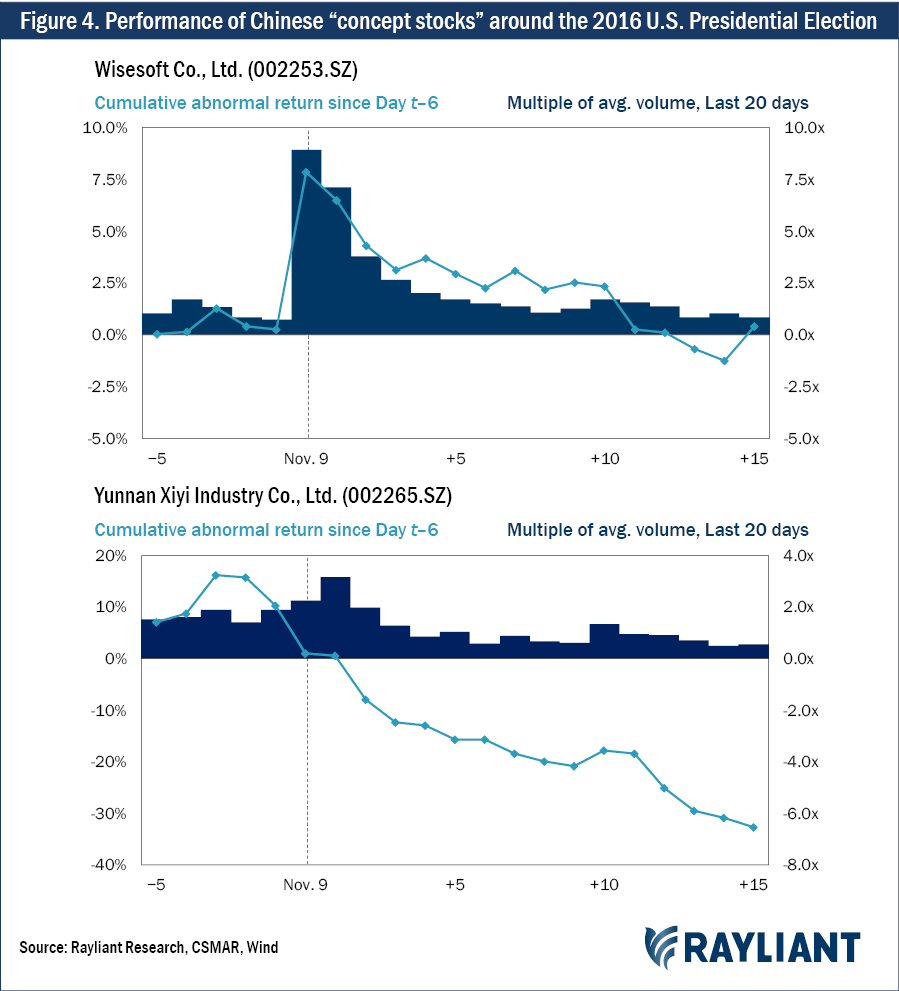

On November 8, 2016, votes were being counted in the US presidential election and the Chinese stock market was already open. A company called Wisesoft Co., Ltd. (002253.SZ), a developer of systems for air traffic controllers, was up big on nearly ten times its average daily volume. Meanwhile, an auto parts manufacturer, Yunnan Xiyi Industry Co., Ltd. (002265.SZ), was crashing hard on double the usual trading. Did the fates of these businesses somehow hinge on the election results on the other side of the planet? Not quite.

As it turns out, Wisesoft’s Chinese name, 川大智胜 (“chuān dà zhì shèng”), is phonetically similar to the phrase “Trump wins big”. (“Trump” is often translated as 川普, “chuān pǔ”.) Yunnan Xiyi, 希姨股份 (“xī yí gǔfèn”), sounds a lot like “Aunt Hillary”. (Clinton’s first name is often expressed as 希拉里, “Xī lā lǐ”.)

Retail investors in China seem to have observed the results of the U.S. election and searched for the stocks that allowed them to express a simple idea: Trump won, Hillary lost. Not terribly deep analysis, but as Figure 4 makes clear, the results of this uninformed trading persisted for weeks: Wisesoft’s election day gains evaporated and Yunnan Xiyi shed 30%—wiping out profits accrued in the weeks leading up to voting, when Chinese investors apparently agreed that Hillary was a shoo-in for the presidency. So much for the wisdom of crowds.

Examples like these are amusing, but they also highlight the massive opportunity presented by an emerging market where non-professionals trade as much for entertainment as for maximizing profits.

Returning to the poker analogy, it’s as though pretty much every player at the table is placing bets without even looking at the cards. They contrast with those who carefully calculate the odds—flagging stocks likely to be overvalued by irrationally exuberant retail traders; identifying firms with bad governance and poor managers; and digging deep into the financial data for evidence of weakness in business fundamentals or signs that positive reports are the outcome of aggressive accounting, maybe even outright fraud. For those playing a well-researched strategy, that seems like a very interesting game indeed.

Subscribe to receive the latest Rayliant research, product updates, media and events.

Subscribe

Sign upIssued by Rayliant Investment Research d/b/a Rayliant Asset Management (“Rayliant”). Unless stated otherwise, all names, trademarks and logos used in this material are the intellectual property of Rayliant.

This document is for information purposes only. It is not a recommendation to buy or sell any financial instrument and should not be construed as an investment advice. Any securities, sectors or countries mentioned herein are for illustration purposes only. Investments involves risk. The value of your investments may fall as well as rise and you may not get back your initial investment. Performance data quoted represents past performance and is not indicative of future results. While reasonable care has been taken to ensure the accuracy of the information, Rayliant does not give any warranty or representation, expressed or implied, and expressly disclaims liability for any errors and omissions. Information and opinions may be subject to change without notice. Rayliant accepts no liability for any loss, indirect or consequential damages, arising from the use of or reliance on this document.

Hypothetical, back-tested performance results have many inherent limitations. Unlike the results shown in an actual performance record, hypothetical results do not represent actual trading. Also, because these trades have not actually been executed, these results may have under- or over- compensated for the impact, if any, of certain market factors, such as lack of liquidity. Simulated or hypothetical results in general are also subject to the fact that they are designed with the benefit of hindsight. No representation is being made that any account will or is likely to achieve profits or losses similar to those shown. In fact, there are frequently sharp differences between hypothetical performance results and the actual results subsequently achieved by any investment manager.

You are now leaving Rayliant.com

The following link may contain information concerning investments, products or other information.

PROCEED