Investors excited by Europe’s “rearmament trade” should tread carefully. The recent surge in European defense shares looks hard to sustain because the spending story behind it is weaker than headlines suggest. The problem is that Europe will not undertake a serious rearmament because it cannot afford to. The arithmetic is unforgiving.

The European Union is, in effect, structurally insolvent. Its states are already overwhelmed with unfunded liabilities, with pensions and healthcare alone measured in the tens of trillions. Demographic decline makes this burden worse every year. Against this backdrop, the idea of sustainably raising defense spending by several percentage points of GDP while preserving welfare systems is implausible, from our perspective.

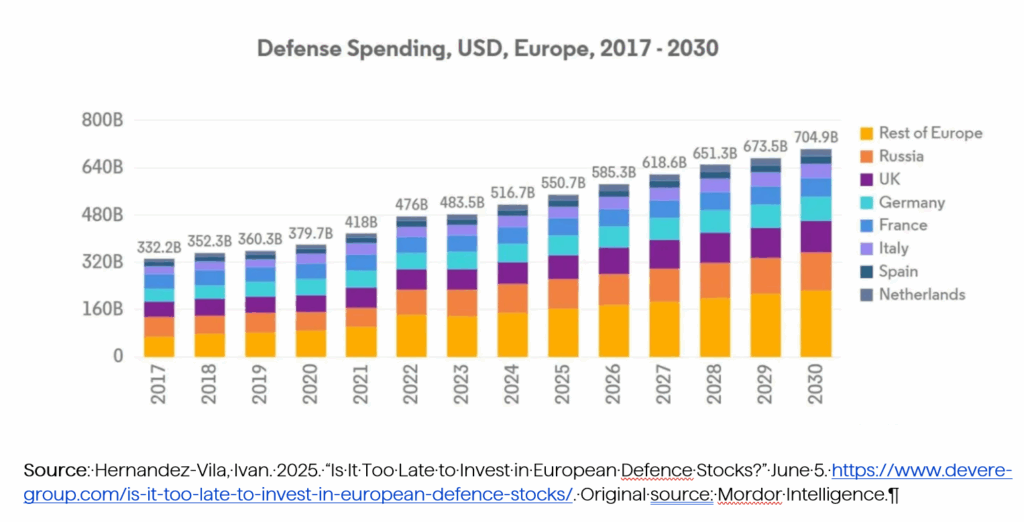

EU defense spending has ticked up from 1.5% of GDP in 2024 to a projected 2.1% this year, with Goldman Sachs forecasting 2.4% by 2027. However, those increases barely scratch the surface of the problem. After decades of underinvestment, a true rebuilding would require something on the scale of a Marshall Plan—an estimated €1.5–2 trillion over the next decade. No one has budgeted for this.

Much of what has been allocated depends on creative accounting, funded by off-balance-sheet vehicles that utilize debt. Even Germany’s much-trumpeted €100 billion special fund is expected to run dry by 2026.

Germany in particular illustrates the problem. Unless there is shooting on its borders, Berlin will continue to lag, relying on Poland’s actual real commitment and, increasingly, on France and Britain’s nuclear umbrellas as questions grow about American guarantees.

Ukraine has proved the limits of European resolve. Supposedly Europe’s wake-up call, the war has instead shown how little appetite there is for true rearmament. Only the UK delivered consistently on its promises. France and Germany hesitated, delayed, or diluted their commitments. French equipment was also found to be lacking in the recent spat between India and Pakistan.

That record has not gone unnoticed abroad. The UK has secured major export wins, including the next-generation fighter program with Japan, as well as large warship contracts from Norway, Canada, Poland, and Australia—often at France’s expense. The lesson for potential export customers is clear: when it comes to credibility as a defense supplier, the UK has pulled ahead while France, Germany, and even the United States have lost ground.

All of this would matter more if Russia were on track to become a dominant threat. But the reality is the opposite: Russia looks more like a state sliding toward failure.

Military spending officially stood at 7.1% of GDP in 2024, although the actual figure is higher when hidden costs are factored in—an unsustainable drain on the civilian economy. Inflation runs hot, interest rates remain punishingly high, and the government is already preparing tax hikes. This is the profile of a state starving its private sector to keep the war machine running.

The energy sector, Russia’s lifeblood, is also under strain. Ukraine’s drone strikes have disrupted nearly a fifth of refining capacity, while sanctions and a lack of technology block much-needed investment. As the Wall Street Journal recently observed, oil output is set for a slow decline.

Meanwhile, Russia’s demographics are collapsing. Births fell to record lows in 2024, while war deaths, emigration, and aging erode the labor force. Increasingly, Moscow relies on mobilizing peripheral ethnic regions, a reminder that the Russian Federation is less a stable nation-state than the brittle core of a fading empire.

Investors (and policymakers) hoping for a robust European rearmament cycle are likely to be disappointed. Fiscal constraints, political resistance, and institutional hesitancy mean Europe will not deliver on its rhetoric. Russia, meanwhile, is not a rising adversary but a weakening one—dangerous in its instability rather than its strength. Hence, the European defense boom looks overstated, and its foundations are far shakier than markets currently assume.

Of the investable opportunities, the UK stands out as an exception, with its firms securing export orders and its government demonstrating reliability. However, the listed companies appear expensive, and there are likely to be more macroeconomic problems in the country as the currently deeply unpopular left-wing government continues to spectacularly unravel until the next scheduled elections in 2029. The good news is that this might prove a good entry point, and the next government is likely to take defense far more seriously than those of the past 30 years.

Disclosure: This material is for informational purposes only and should not be considered investment advice. An investor should consult with their financial professional before making any investment decisions. The opinions contained herein are subject to change without notice and do not necessarily reflect the opinions of Rayliant Investment Research. Indices cannot be invested in directly and are unmanaged.

You are now leaving Rayliant.com

The following link may contain information concerning investments, products or other information.

PROCEED