Insights, Research

Phillip Wool, PhD

Scroll downChina’s mainland mutual fund market is interesting for a number of reasons, not least the fact that, with amateur traders accounting for 80-90% of volume, we naturally expect professional fund managers to show consistent outperformance. That makes China a great place to study mutual fund manager ability and field test tools for selecting exceptional funds. In this research note, we review some of the history behind China’s asset management industry, describe a number of the market’s most striking features from the perspective of a foreign investor, then take a close look at the nature of manager skill among onshore mutual funds. Our results shed light on the sources of mutual fund outperformance in China and demonstrate the value of active management in a market dominated by retail investors.

In developed markets, decades of research have shown that despite great marketing and dramatic press accounts of the occasional hedge fund superstar, the average active manager loses money for their clients after fees.1 In the last ten years, US investors seem to have finally got the message, as $185 billion flowed out of active funds, while passive strategies saw inflows of $3.8 trillion.2 For those considering an active approach in the pursuit of market-beating returns, such data points are clearly discouraging. In this research note, I’ll describe more hopeful findings from a vastly different group of money managers: the nearly 8,000 funds making up China’s US$3 trillion mutual fund industry.

Although many features of the way Chinese asset management has evolved will likely strike foreign investors as strange, mispricings in China’s retail-driven stock market provide talented mutual fund managers with an opportunity to generate persistent alpha. The presence of skilled funds with a consistent edge demonstrates that active management can still be an effective way to earn extraordinary returns in less efficient markets—great news for investors considering an allocation to mainland Chinese stocks. Before diving into the dynamics of Chinese equity managers’ skill and outperformance, it will be useful to consider the meteoric rise of China’s funds industry and to highlight distinguishing characteristics of the way money is managed by domestic players in the world’s second-largest stock market.

The Shanghai and Shenzhen stock exchanges launched in 1990, but it wasn’t until the late ’90s that regulators established clear rules for securities investment funds. Before that, the early days of China’s asset management industry were a veritable Wild West. For example, Chen, Xiong, and Huang (2015) recount the story of 24-year-old stock analyst Chenggang Sun, who in 1993 began tacking his equity research onto the bulletin board inside a Shandong trading hall. Within a year, he had founded Shenguang Investment Advisory Co. to run outside money, quickly becoming one of the most influential advisors in China. After a regulatory reprimand in 2004, Sun soon reemerged hawking stock trading tutorials on CD-ROM, advertising 100x returns, eventually founding another advisory firm.

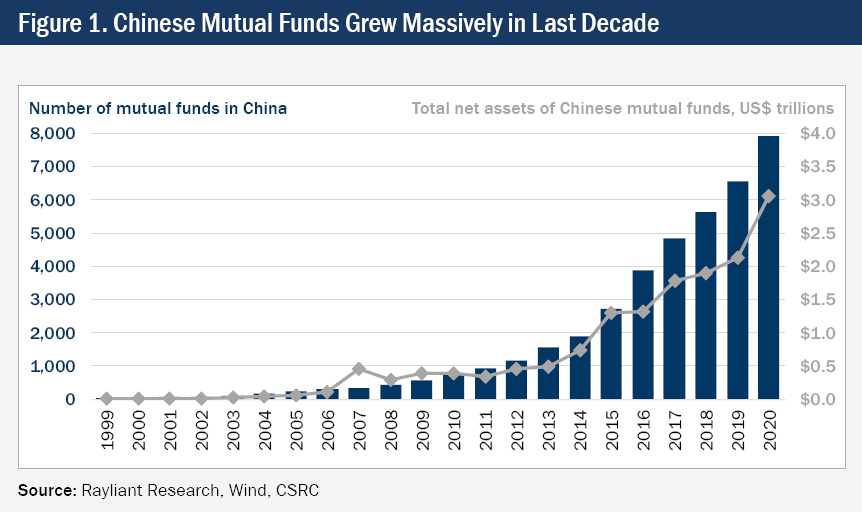

Fast forward to 1997: China’s State Council, under pressure to regulate a burgeoning fund management industry, finally issued legislation explicitly governing investment funds. Around the same time, the China Securities Regulatory Commission (CSRC)—often thought of as China’s answer to the SEC—was appointed to operationalize those rules. This new structure provided a solid foundation for two decades of breakneck growth, with China’s asset management industry rocketing from a mere 22 funds in 1999 to 7,913 funds at the end of 2020, managing just over US$3 trillion in assets (see Figure 1). Underscoring the accelerating expansion of China’s fund assets in recent years, the launch of a single strategy in January 2021 was oversubscribed to the tune of almost 16x its fundraising cap, with a whopping US$37 billion promised to the manager by investors in its first day of sales.

Despite greater regulation and trillions in AUM, asset managers have preserved some of the eccentric entrepreneurial spirit that characterized the industry in its formative years. Even today, some of the country’s top domestic fund managers livestream to hundreds of thousands of online followers, giving away cash and bottles of expensive booze to attract attention from prospective retail clients—many of whom can invest with the click of a link on smartphone apps connected to their financial accounts.3 And it’s not all hype: With amateur traders accounting for roughly 85% of volume in individual stocks as of 2020, it’s not surprising that professional managers have shown a long history of outperformance versus the broader market, easily rationalizing the flood of assets into active funds over the last decade.4

It’s hard to imagine a US asset manager advertising funds through online prize giveaways, although the way funds are promoted isn’t the only difference between money management in the US and China. Investment style is another key distinction. Foreign investors considering domestic mutual funds will likely be shocked with the level of trading done by Chinese equity managers, with annual turnover averaging upward of 200% historically, and many funds churning portfolios by over 1,000% per year, compared to average US mutual fund turnover of just 56%.5 Offshore allocators will also be surprised with the prominence of so-called “hybrid” funds, which actively move between cash and equities to time the market. In China, such funds make up nearly 70% of assets invested in active equity strategies as of the end of 2020, versus just 11% of assets in US stock funds.6 As we’ll see, this proclivity for market timing by Chinese funds turns out to be an important component of local fund managers’ skill.

Differences in regulation also contribute to the way Chinese funds manage money, with the PRC’s paternalistic approach to financial policy often giving way to unintended consequences. Mutual fund fees aren’t explicitly controlled by regulators, for example, though fund managers trying to capitalize on exceptional skill by charging more or those seeking a competitive edge through lower fees will often find their applications rejected on the grounds that such pricing is exploitative or disruptive. The upshot is that most mutual funds—regardless of size, quality, or brand appeal—charge similar fees and, as a result, typically see their most talented analysts poached by hedge funds that don’t face such restrictions and can afford to pay much better. Fund launches in China also entail significant red tape, with new products undergoing a tightly regulated IPO process that leads to most of a fund’s AUM coming in at the time it launches. Rather than grow revenues by nurturing a strategy and seeing AUM scale up over time, this leads many asset managers to constantly launch new thematic funds, jumping from one hot investment narrative to another in dramatic “boom-bust” cycles.

Finally—and perhaps most importantly for those considering an allocation to Chinese stocks—while academic research into US mutual fund manager skill has turned up rather disappointing results, many studies have found mutual funds in China to consistently outperform.7 Of course, the apparent absence of alpha among US managers might not be a matter of talent, but rather a question of who else is playing the game. Prior to the recent surge in US retail trading, professional investors made up roughly 95% of trading volume, such that skilled money managers were more likely than not facing off against one another, with neither side of a trade likely to give up much edge. In China, with 80-90% of trades placed by amateur investors, the pros have greater opportunity to identify and exploit mispricings, which makes it easier for funds’ ability to show. The fact that we expect to find alpha earners in China makes it a great place to sharpen tools for spotting the best managers and learn more about the sources of their outperformance.

How does one identify skilled money managers before they post big returns? Investors often chase past performance, hoping it repeats. Unfortunately, noisy returns make that a nearly hopeless exercise, even for managers with longer-than-average track records—and especially for China’s relatively short-lived funds. In research done in collaboration with my colleague, Jason Hsu, and our co-authors, Brad Cornell and Patrick Kiefer, published last year in the Journal of Portfolio Management, we described a new method for selecting exception managers, using China’s inefficient equity market as our proving ground.8 Details on the methodology are in the paper, but we’re effectively using changes in funds’ holdings to spot managers with a knack for making prescient trades. China’s stock market is so inefficient that picking a random fund would have delivered positive alpha over our sample. A better test of our approach is whether the funds we rate as exceptional go on being exceptional after we’ve chosen them.

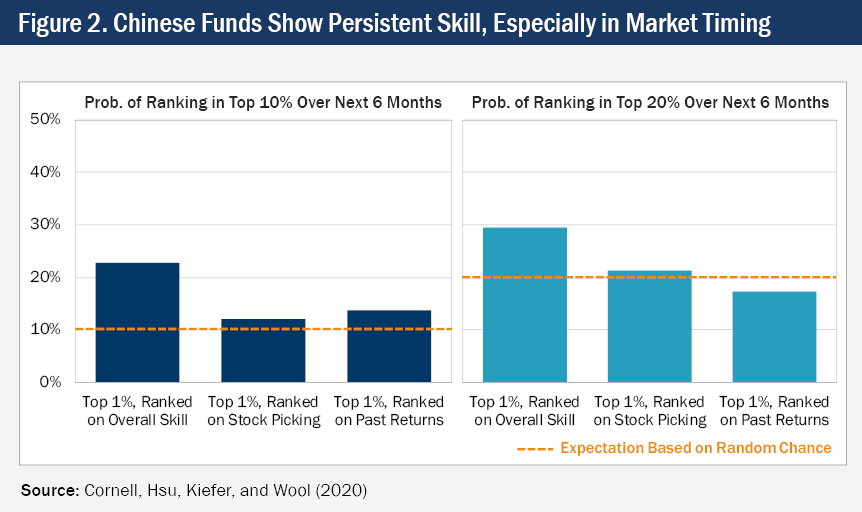

To that end, the leftmost bar in the left panel of Figure 2 presents in simple terms the central finding of our study. Using data from the past six months, we rank all Chinese mutual funds on skill according to our measure and pick out the top 1% of all funds, which we’ll refer to as “exceptional” money managers. By mere chance, one would expect a randomly picked fund to have top-decile performance over the next six months with 10% probability. Our exceptional funds have a 23% of chance of ranking in the top decile. By contrast, a fund with returns in the top 1% of all funds—truly exceptional past performance—will go on to earn top-decile returns over the next half year with only 14% probability (third bar in the left panel). Drilling the point home, the righthand panel shows the likelihood of picking funds in the top quintile, where our methodology picks future outperformers with almost 30% probability, while selecting on past returns was actually worse than throwing darts at a list of managers. One conclusion from this research is that finding exceptional managers in a market rife with alpha is a worthwhile pursuit, although grading funds on past performance alone won’t yield the best results going forward.

In our paper, we described another convenient feature of our methodology for identifying exceptional managers: it’s quite easy to decompose our overall measure of skill into stock picking ability and talent for market timing. In Figure 2, the middle bar in each panel shows the probability that a manager with exceptional stock picking ability goes on to have top-ranked performance over the next six months. The results here are much less impressive; it seems that past stock picking skill does no better than dumb luck at picking next period’s winners. This suggests that most of the performance persistence among Chinese fund managers comes not from their skill at selecting stocks, but from their success in timing their exposure to the market. I mentioned the popularity of hybrid funds before, and that’s likely one of the reasons we see more rewards to timing ability than stock selection skill for Chinese fund managers. If demand for dynamism leads a fund to allocate most of its risk budget to market timing, even the best stock picker would have trouble adding alpha—an interesting case of client preferences and fund company culture combining to influence the way money is managed.

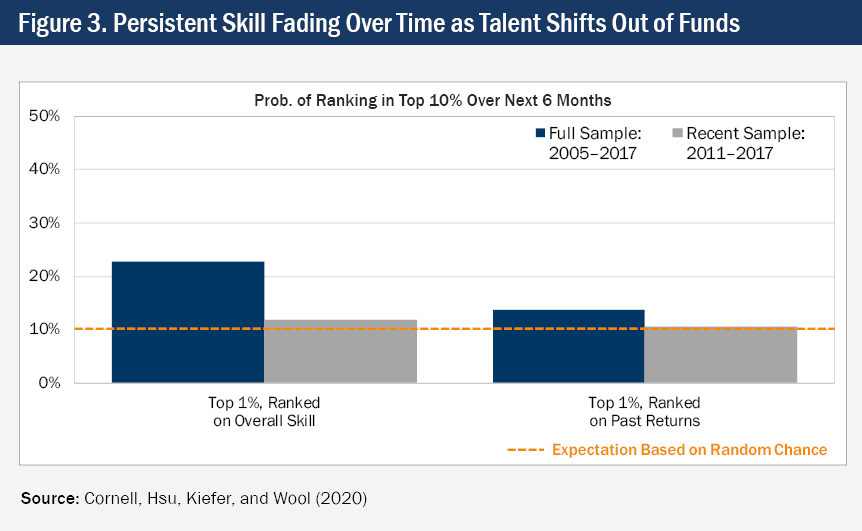

One last observation about manager skill in China’s mutual fund industry is presented in Figure 3, again comparing selection of exceptional managers based on our approach to selection on the basis of past returns, but now showing the results of that test for our full sample (2005–2017, blue bars) and a more recent subsample (2011–2017, gray bars). It’s clear that our methodology is far less effective in recent years, only modestly beating out past performance and random selection at identifying top funds in the second half of our sample. Those familiar with the evolution of fund management in China will appreciate one likely culprit in this shift, alluded to in our discussion of how Chinese funds raise assets and charge fees: the exodus of managers from mutual funds to hedge funds in search of better compensation. In short, because regulation keeps fees fairly static and the way funds are sold usually leads AUM to peak near a fund’s launch, regardless of subsequent performance, fund companies have trouble retaining talent when a strategy succeeds. With individual manager turnover rates in China running at 10-20% per annum9, it stands to reason past fund performance and holdings characteristics—determined by the last manager at the helm, not the current team—will be less helpful in scoring funds. The alpha’s still there, it’s just not being captured by domestic mutual funds.

Setting aside the colorful history of China’s asset management industry and the interesting differences between Chinese and US funds, the presence of detectable skill among onshore mutual funds serves as another point of evidence in favor of the alpha opportunity for investors putting money to work in China’s mainland stock market. In that sense, this research attacks the question of available alpha from a new angle, complementing analysis we’ve written about elsewhere showing that simple quant strategies yield greater outperformance in markets, like China’s, with higher retail participation.10 Of course, for offshore investors seeking to tap into this alpha stream, the interaction we’ve highlighted between local investment culture and a unique regulatory approach makes understanding China’s nuanced investment landscape critical in selecting the right managers.

1 Studies showing an absence of skill on the part of US mutual fund managers go all the way back to Jensen (1968), published when the Efficient Markets Hypothesis was still in its infancy. Decades of subsequent research have confirmed a lack of persistent outperformance (e.g., Malkiel 1995; Gruber 1996; Carhart 1997; Zheng 1999; Bollen and Busse 2001; Fama and French 2010), although—as is often the case on the subject of market efficiency—there are plenty of studies challenging this view with evidence that at least some managers show skill (e.g., Grinblatt and Titman 1989; Wermers 2000; Chen, Jegadeesh, and Wermers 2000; Kosowski et al. 2006; Kacperczyk, Sialm, and Zheng 2008; Cremers and Petajisto 2009; Berk and van Binsbergen 2015).

2 As reported by Morningstar (2021)

3 Bloomberg (2020) offers an entertaining account of the struggle many foreign money managers have experienced adapting to China’s retail funds ecosystem.

4 In research with coauthors, which I’ll spend more time describing momentarily, we found the average Chinese mutual fund returned 16.7% per annum versus 13.9% per year for the widely tracked CSI 300 index, from June 2005 through December 2017 (Cornell, Hsu, Kiefer, and Wool 2020).

5 Chinese data come from Jiang and Kim (2015), US data come from the Investment Company Institute (2019).

6 Chinese data calculated from AMAC data via Wind; US data from the Investment Company Institute (2020).

7 Studies finding evidence of mutual fund manager skill include: Yi and He (2016); Liao, Zhang, and Zhang (2017); and Koutmos, Wu, and Zhang (2020). As with the literature on US fund manager ability, a number of studies also report the opposite—that Chinese funds cannot deliver value net of fees—including those by Sherman, O’Sullivan, and Gao (2017) and Yang and Liu (2017).

8 See Cornell, Hsu, Kiefer, and Wool (2020) for an expanded description of the methodology and more detailed discussion of our findings.

9 Huang, Liang, and Wu (2019)

10 Hsu, Liu, and Wool (2020) test a range of simple factor strategies in emerging and developed markets, finding greater alpha in markets for which retail trading makes up a greater proportion of overall volume. A condensed version of the paper is available here.

Berk, Jonathan B., and Jules H. Van Binsbergen. “Measuring Skill in the Mutual Fund Industry.” Journal of Financial Economics 118, no. 1 (2015): pp. 1–20.

Bloomberg News. “Inside the Cutthroat World of China Mutual Fund Livestreaming.” Bloomberg, December 17, 2020.

Bollen, Nicolas, and Jeffrey A. Busse. “On the timing ability of mutual fund managers.” The Journal of Finance 56, no. 3 (2001): pp. 1075-1094.

Carhart, Mark M. “On persistence in mutual fund performance.” The Journal of Finance 52, no. 1 (1997): pp. 57-82.

Chen, Hsiu-Lang, Narasimhan Jegadeesh, and Russ Wermers. “The value of active mutual fund management: An examination of the stockholdings and trades of fund managers.” Journal of Financial and Quantitative Analysis 35, no. 3 (2000): pp. 343-368.

Chen, Zhiwu, Peng Xiong, and Zhuo Huang. “The asset management industry in China: its past performance and future prospects.” The Journal of Portfolio Management 41, no. 5 (2015): pp. 9-30.

Cornell, Bradford, Jason Hsu, Patrick Kiefer, and Phillip Wool. “Assessing Mutual Fund Performance in China.” The Journal of Portfolio Management 46, no. 5 (2020): pp. 118-127.

Cremers, KJ Martijn, and Antti Petajisto. “How active is your fund manager? A new measure that predicts performance.” The Review of Financial Studies 22, no. 9 (2009): pp. 3329-3365.

Fama, Eugene F., and Kenneth R. French. “Luck versus skill in the cross‐section of mutual fund returns.” The Journal of Finance 65, no. 5 (2010): pp. 1915-1947.

Grinblatt, Mark, and Sheridan Titman. “Mutual fund performance: An analysis of quarterly portfolio holdings.” Journal of Business (1989): pp. 393-416.

Gruber, Martin J. “Another puzzle: The growth in actively managed mutual funds.” The Journal of Finance 51, no. 3 (1996): pp. 783-810.

Hsu, Jason, Xiang Liu, and Phillip Wool. “Should You Have More China in Your Portfolio? Putting Common Arguments for Increased China Exposure to the Test.” The Journal of Index Investing 11, no. 3 (2020): pp. 48-61.

Huang, Ying Sophie, Bing Liang, and Kai Wu. “Are Mutual Fund Manager Skills Transferable to Private Funds?.” Working paper, Central University of Finance and Economics, 2019.

Jensen, Michael C. “The performance of mutual funds in the period 1945–1964.” The Journal of Finance 23, no. 2 (1968): pp. 389-416.

Jiang, Fuxiu, and Kenneth A. Kim. “Corporate governance in China: A modern perspective☆.” Journal of Corporate Finance 32 (2015): pp. 190-216

Kacperczyk, Marcin, Clemens Sialm, and Lu Zheng. “Unobserved actions of mutual funds.” The Review of Financial Studies 21, no. 6 (2008): pp. 2379-2416.

Kosowski, Robert, Allan Timmermann, Russ Wermers, and Hal White. “Can mutual fund “stars” really pick stocks? New evidence from a bootstrap analysis.” The Journal of Finance 61, no. 6 (2006): pp. 2551-2595.

Koutmos, Dimitrios, Bochen Wu, and Qi Zhang. “In search of winning mutual funds in the Chinese stock market.” Review of Quantitative Finance and Accounting (2019): pp. 1-28.

Liao, Li, Xueyong Zhang, and Yeqing Zhang. “Mutual fund managers’ timing abilities.” Pacific-Basin Finance Journal 44 (2017): pp. 80-96.

Malkiel, Burton G. “Returns from investing in equity mutual funds 1971 to 1991.” The Journal of Finance 50, no. 2 (1995): pp. 549-572.

McDevitt, Kevin and Nick Watson. “The decade in fund flows: A recap in 5 charts.” Morningstar, January 29, 2020.

Sherman, Meadhbh, Niall O’Sullivan, and Jun Gao. “The Market-Timing Ability of Chinese Equity Securities Investment Funds.” International Journal of Financial Studies 5, no. 4 (2017): pp. 1-18.

Wermers, Russ. “Mutual fund performance: An empirical decomposition into stock‐picking talent, style, transactions costs, and expenses.” The Journal of Finance 55, no. 4 (2000): pp. 1655-1695.

Yang, Liuyong, and Weidi Liu. “Luck versus skill: Can Chinese funds beat the market?.” Emerging Markets Finance and Trade 53, no. 3 (2017): pp. 629-643.

Yi, Li, and Lei He. “False discoveries in style timing of Chinese mutual funds.” Pacific-Basin Finance Journal 38 (2016): pp. 194-208.

Zheng, Lu. “Is money smart? A study of mutual fund investors’ fund selection ability.” The Journal of Finance 54, no. 3 (1999): pp. 901-933.

Subscribe to receive the latest Rayliant research, product updates, media and events.

Subscribe

Sign upIssued by Rayliant Investment Research d/b/a Rayliant Asset Management (“Rayliant”). Unless stated otherwise, all names, trademarks and logos used in this material are the intellectual property of Rayliant.

This document is for information purposes only. It is not a recommendation to buy or sell any financial instrument and should not be construed as an investment advice. Any securities, sectors or countries mentioned herein are for illustration purposes only. Investments involves risk. The value of your investments may fall as well as rise and you may not get back your initial investment. Performance data quoted represents past performance and is not indicative of future results. While reasonable care has been taken to ensure the accuracy of the information, Rayliant does not give any warranty or representation, expressed or implied, and expressly disclaims liability for any errors and omissions. Information and opinions may be subject to change without notice. Rayliant accepts no liability for any loss, indirect or consequential damages, arising from the use of or reliance on this document.

Hypothetical, back-tested performance results have many inherent limitations. Unlike the results shown in an actual performance record, hypothetical results do not represent actual trading. Also, because these trades have not actually been executed, these results may have under- or over- compensated for the impact, if any, of certain market factors, such as lack of liquidity. Simulated or hypothetical results in general are also subject to the fact that they are designed with the benefit of hindsight. No representation is being made that any account will or is likely to achieve profits or losses similar to those shown. In fact, there are frequently sharp differences between hypothetical performance results and the actual results subsequently achieved by any investment manager.

You are now leaving Rayliant.com

The following link may contain information concerning investments, products or other information.

PROCEED