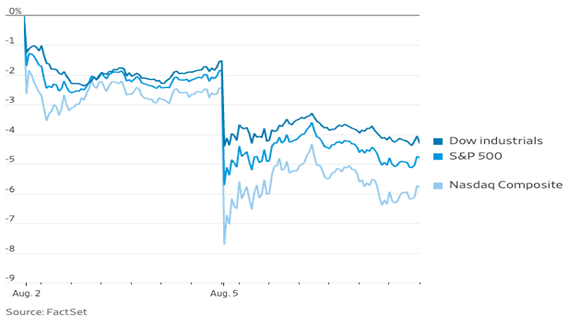

In August 2024, global markets experienced a sudden, violent shudder. A modest rate hike by the Bank of Japan (BOJ) sent the Yen spiking 10%, triggering one of the worst selloffs in Japanese equity history and sending shockwaves through Wall Street. The culprit? The unwinding of the “Yen Carry Trade.”

For decades, Japan has been the world’s ATM—one of the most reliable providers of cheap funding. With interest rates near zero, investors borrowed Yen to buy higher-yielding assets abroad, from US Treasuries to tech stocks. The prevailing fear among US investors is that as Japanese rates finally rise, this massive liquidity engine will reverse. We think the “Bear Thesis” is simple and terrifying: Japanese yields go up, money rushes home, and global asset prices could collapse.

However, this linear “A-leads-to-B” thinking misses the mark. Financial markets are complex systems, not simple circuits. While the risks are real, the mechanics of the Japanese financial system suggest a sudden catastrophe is less likely than a slow, manageable grind. Here is why the “Great Unwind” might not happen the way doomsayers predict.

The first misunderstanding concerns how Japanese institutions actually invest. The bears assume that if Japanese bond yields rise, US bonds and other assets become less attractive. But Japanese insurers and banks rarely buy US Treasuries on a naked basis; they hedge currency risk to some degree.

We believe the cost of this hedging is driven by short-term interest rate differentials. Paradoxically, if the BOJ raises rates while the Fed holds steady, the interest rate gap narrows, and the cost of hedging falls. This could create a counterintuitive outcome: as Japanese rates rise, the net yield (after hedging) on US assets might actually improve, making them more attractive, not less. The signal that “Japan is normalizing” could easily be drowned out by the reality that hedging US debt has become cheaper.

There is also a structural mismatch that prevents a wholesale repatriation of capital. Japanese life insurers hold liabilities that stretch out 20 to 30 years. They need long-term assets to match these obligations.

The problem? The domestic market in Japan cannot satisfy this demand. The BOJ owns a massive chunk of the bond market, and there is insufficient supply of long-dated Japanese Government Bonds (JGBs) to absorb the trillions of Yen currently invested abroad. Even if a Japanese insurer wanted to bring its money home, it would be swapping a 30-year US Treasury for a 10-year JGB with inadequate duration. Until Japan’s fiscal policy changes drastically, these institutions are structurally forced to lend to the United States.

The bears also fundamentally misunderstand the changing face of the Japanese retail investor. For years, the market has fixated on “Mrs. Watanabe”—the metaphorical housewife trading FX on high margin. This demographic is indeed flighty; in August 2024, they were forced to liquidate leveraged positions, accelerating the Yen’s spike.

But while Mrs. Watanabe panics, a new, far larger whale has entered the pool: the NISA investor.

In January 2024, the Japanese government massively expanded the Nippon Individual Savings Account (NISA) program, incentivizing households to shift their $14 trillion in cash savings into the stock market. Unlike the day-trading FX crowd, these are long-term, structural investors. And crucially, they don’t want to own Japanese assets at present.

Since the program’s expansion, Japanese retail investors have been pouring approximately ¥1 trillion ($6.2 billion) per month into foreign investments, primarily US and global equity funds. This is “sticky” money—monthly automated contributions that are largely insensitive to short-term currency swings.

This creates a permanent structural bid for foreign assets that we believe directly counteracts the repatriation thesis. Every time a speculator sells USD to buy Yen, a Japanese salaryman’s NISA account automatically sells Yen to buy USD. The bears see a tsunami of repatriation; they miss the steady, relentless current of retail capital flowing the other way.

Furthermore, we cannot ignore the accounting realities that govern bank behavior. Many Japanese institutions hold foreign bonds that are currently underwater (trading below purchase price) due to the global rise in rates.

Under Held-to-Maturity (HTM) accounting rules, these losses are ignored as long as the bonds are not sold. This is common practice with US banks too. In fact, US banks are currently sitting on $337 billion of unrealized bond losses themselves. If these banks were to sell their US Treasuries to repatriate cash to Japan, they would crystallize those losses immediately, damaging their balance sheets and capital ratios. Doing nothing is safer for management than taking action. This creates a powerful inertia—a “do-nothing equilibrium” in the hope that things improve, that prevents panic selling.

Finally, we must remember that central banks prioritize financial stability above all else. We saw this clearly in August 2024: the moment the markets revolted, the BOJ blinked, with Deputy Governor Uchida pledging no further hikes amidst instability.

The system has circuit breakers. If a disorderly unwind threatens the global financial plumbing, expect coordinated intervention. The BOJ manages the global cost of capital, and they are unlikely to tolerate a spike in yields that would blow up their own domestic banks.

We believe the Yen Carry Trade is indeed a critical part of the global financial architecture, and its nature is changing, while its unwinding does pose risks. However, the transmission mechanism is clogged by accounting rules, duration shortages, and commercial and behavioral incentives.

For US investors, the likely scenario is not a “sudden phase transition”—a crash, in other words—but a gradual adjustment over the next decade. The “widowmaker” trade of shorting Japanese bonds has failed for decades because it bets on a breakage that authorities work tirelessly to prevent.

Rather than fearing a sudden collapse, keep an eye on the “plumbing”—specifically the cross-currency basis and hedged yields. Until those indicators flash red, the flow of Japanese capital is likely—at best—to drift, rather than crash.

Disclosure: This material is for informational purposes only and should not be considered investment advice. An investor should consult with their financial professional before making any investment decisions. The opinions contained herein are subject to change without notice and do not necessarily reflect the opinions of Rayliant Investment Research. Indices cannot be invested in directly and are unmanaged.

You are now leaving Rayliant.com

The following link may contain information concerning investments, products or other information.

PROCEED