“It’s now a question of, is it the manufacturer, is it the retailers, or is it the

small business that’s bringing [goods] in? They now have to figure out,

‘How much of this can I take on, and how much of this will I pass on?’

It’s very likely they will pass the bulk of it on.”

—Olu Sonola, Head of US Economic Research at Fitch Ratings, interviewed by CNN

Among the macro themes at the front of investment strategists’ minds in 2025 has been Trump 2.0 trade policy, the impact this year’s tariffs could have on the economy and, ultimately, how that will play out in investors’ portfolios. Before and immediately after a “Liberation Day” onslaught of levies on goods from countries across the globe, most pundits speculated new trade frictions—what amount to the biggest US tariffs in nearly a century—would exert a “stagflationary” influence: boosting prices and simultaneously stunting economic growth. Those fears led to an early-April selloff in stocks as traders priced in economists’ worst fears.

That reaction turned out to be premature. Prices did not immediately skyrocket, growth didn’t slump, and stocks—both in the US and, even more so, in international markets—bounced back sharply. In part, that’s because the big “headline” tariff announcements gradually gave way to delays, temporary reprieves, and the kind of high-profile dealmaking President Trump clearly relishes. In time, investors taking stock of how threats of a trade war in principle were actually playing out in practice came to strongly discount the likelihood of a trade-induced recession.

Of course, in the months since tariff talk began, we’ve had a chance to observe plenty of data beyond CPI and GDP, and some of what we’re seeing casts doubt on the bullish narrative that investors ought to always “buy the dip” because tariffs aren’t so bad after all. For one thing, while the Trump administration has been open to delaying levies and cutting deals, effective tariffs even accounting for that slack in the policy are nonetheless extremely high. At the end of October, the Yale Budget Lab estimated overall average effective tariffs at 17.9%, the highest level since 1934.

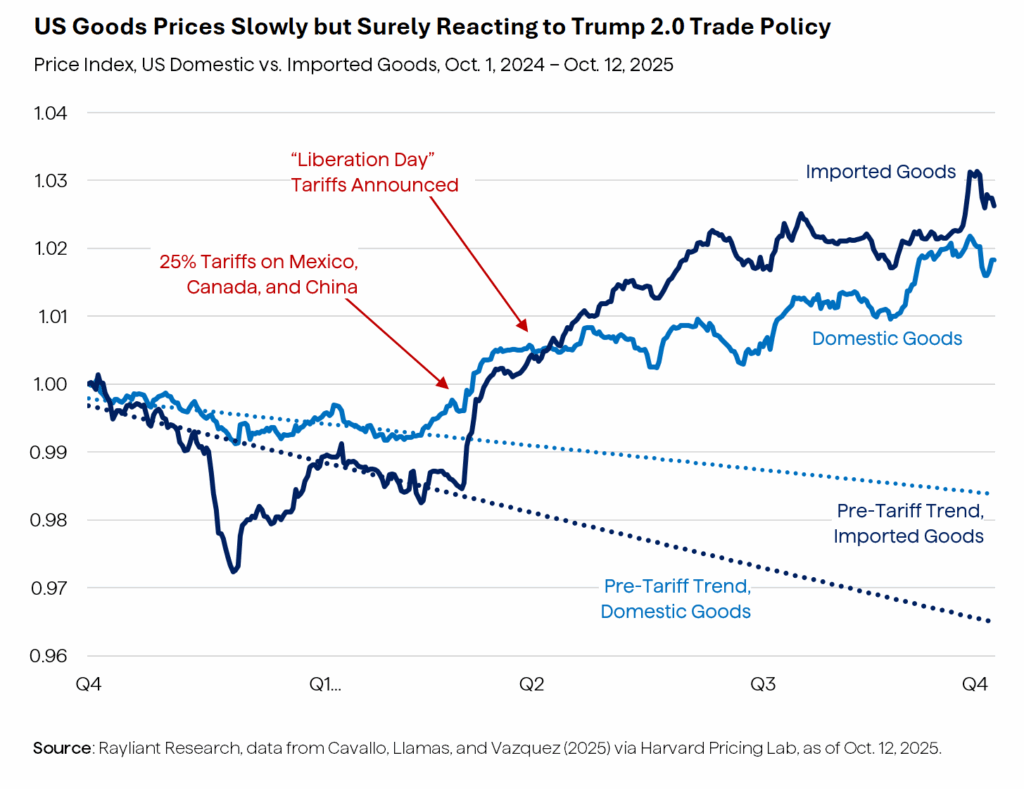

More granular data on prices show, moreover, that those historically high barriers to trade are having an impact. Data from the Harvard Pricing Lab, (plotted below), show prices on imported goods into the US steadily climbing since the Q1 imposition of tariffs on Mexico, Canada, and China, reversing a negative trend going into this year. What’s even more interesting is that domestic US goods prices, which one might imagine wouldn’t inflate as protectionist policies made them more competitive, actually have risen, staying just a tad cheaper than their imported counterparts. Tariffs’ toll on import prices have effectively given US manufacturers cover to boost their own margins, and they’ve understandably taken advantage.

One reason the impact on inflation has been fairly muted so far is that US companies, going into the year with healthy margins themselves and bigger inventories from an effort to front-run “Liberation Day,” decided to absorb a good chunk of rising prices themselves—Goldman Sachs estimates firms ate just over half of the new tariff costs through August—shielding consumers at the expense of their own profitability. But that’s no more than a temporary fix, essentially a bet on the trade war being short-lived, which must inevitably give way as investors penalize stocks whose earnings growth has stalled. Likewise, the inventory of pre-tariff goods imported earlier this year is, at this point, likely largely spent, making it that much harder for firms to keep prices low.

Now, as companies find it harder to contain the influence trade policy has on prices, the impact ultimately plays into another big macro theme this year: the Fed’s plans for continued cuts to US policy rates. If inflation does begin to bite, that could put a hamper on plans to keep easing, reducing accommodation at the same time consumers feel the pain of higher prices and US companies see profits fall further. And it’s obvious that investors have concerns about the FOMC’s endgame. We saw it in mid-November, when Minneapolis Fed President Neel Kashkari rattled markets with a mere mention of some doubts that a December cut was warranted.

But how worried are investors that trade policy could lead to this sort of economic reckoning? Back in April, when tariff fears were front-and-center, traders seemed attuned to such risk: 80% of money managers surveyed by Bank of America nominated a “global recession triggered by a trade war” as the top tail risk facing the markets. By October, however, only 5% of respondents still thought that was the biggest risk. Now, as the US government comes out of its shutdown and new statistics roll in, investors might want to reevaluate once again. Data from the Commerce Department released in mid-November, for example, showed imports of goods and services to the US fell by 5.1% in August—just the first month, we note, in which new tariffs on around 90 countries went into effect.

Disclosure: This material is for informational purposes only and should not be considered investment advice. An investor should consult with their financial professional before making any investment decisions. The opinions contained herein are subject to change without notice and do not necessarily reflect the opinions of Rayliant Investment Research. Indices cannot be invested in directly and are unmanaged.

You are now leaving Rayliant.com

The following link may contain information concerning investments, products or other information.

PROCEED